There was sad news recently for many admirers of the original two-wheeled tourer: the Gold Wing Road Riders’ Association is closing after 45 years of service to Honda’s mighty mile-muncher.

The last ever Wing Ding rally took place in June in Shreveport, Louisiana, attended by far fewer riders than in the GWRRA’s heyday, when the organisation had more than 80,000 members in over 50 countries.

Most touring riders prefer adventure bikes these days, it seems, even in the States. Or maybe it’s just that many “Wing Nuts”, as members call themselves, are getting too old to ride.

Either way, there’s no disputing the impact that Honda made in 1975 with the launch of the GL1000 Gold Wing, which revolutionised long-distance motorcycling and arguably generated more controversy than any bike before or since.

“Two Wheeled Motor Car?” sneered Bike, Britain’s best-selling monthly, before describing the Wing as ugly, overweight, too complicated and boring. That was enough to lose the magazine Honda’s advertising for a year.

Not all UK reviewers were so negative but the reaction was very different in the US where Cycle, the best-selling title, began a rave review with: “If Honda is going to sell a motorcycle for $3000, then by all that’s holy it’s going to be worth it.” Soon the Wing was on its way to becoming not just a Stateside sales success but a two-wheeled phenomenon.

Riding a well-maintained GL1000 years later, the slightly weird thing is how ordinary it seems. Despite its high bars, bulbous styling and big flat-four engine, this 1976-model GL is more noticeable for its vivid yellow paint than its size. Cruising along at a lazy 60mph, it feels far too inoffensive to have been remotely controversial.

By modern touring standards the GL1000 is not so much complex and overweight as basic and under-equipped. It has no fairing or luggage; no radio, cruise control or reverse gear – let along the fancy sound system, satnav, heated seats or countless other features that so many bikes now have as standard.

Bikes were very different in the early Seventies, when a group of Honda engineers led by Shoichiro Irimajiri – legendary designer of the firm’s multi-cylinder race bikes of the previous decade – sat down to plan the “King of Motorcycles”. The new model was to be the world’s fastest and best; a grand tourer that would bring back to Honda the glory that the CB750 four was set to lose to Kawasaki’s recently launched 900cc Z1.

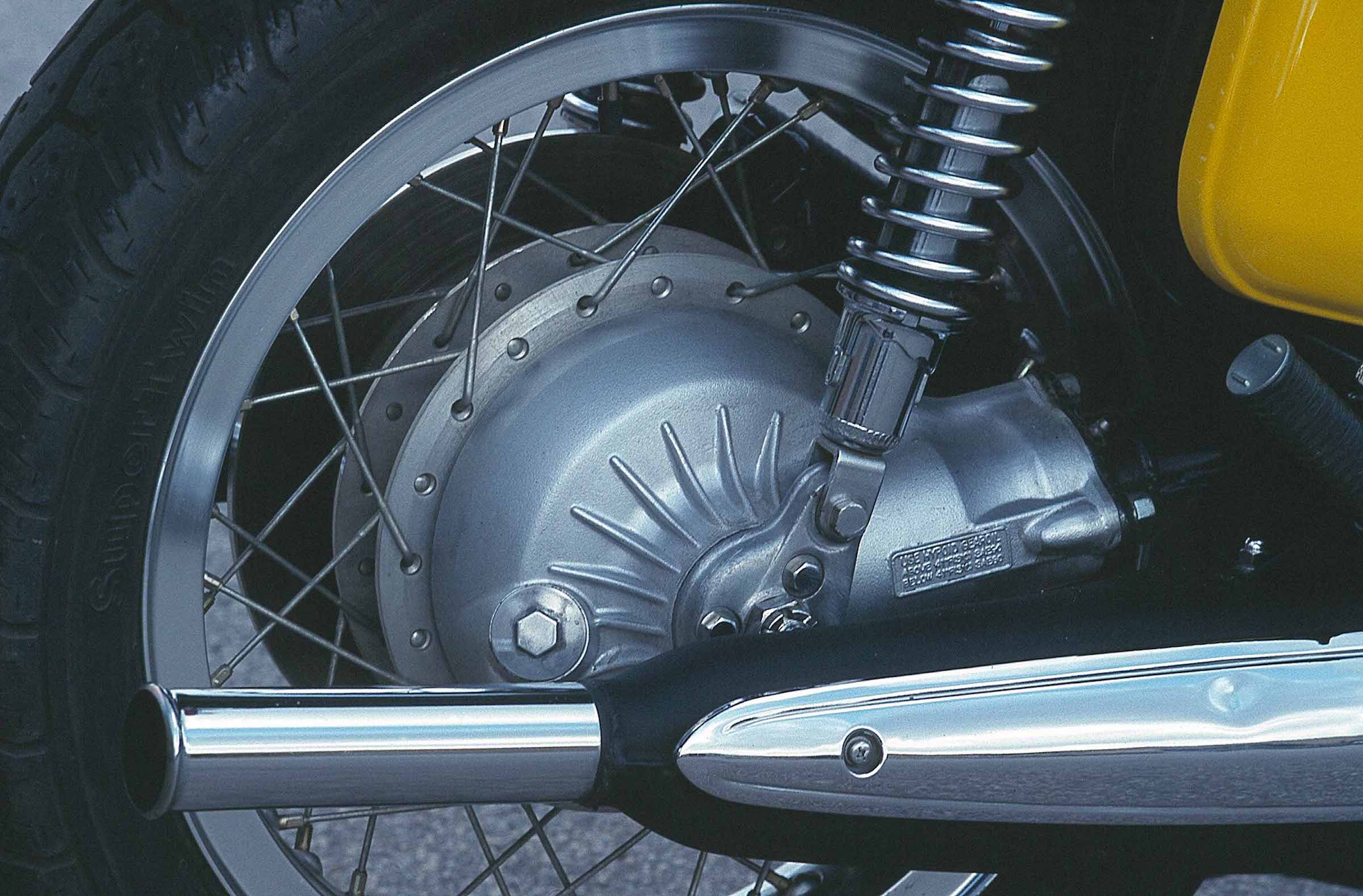

After rejecting a flat-six engined prototype, Irimajiri and his team opted for a 999cc flat-four unit that produced 80bhp. It was the first liquid-cooled four-stoke from a Japanese manufacturer, and the first shaft-drive unit for export markets. Its single overhead camshafts were driven by toothed rubber belts, a first for a bike motor.

The tubular steel-framed chassis was relatively conventional, notable mainly for the dummy fuel tank that contained some electrical components, a kickstart lever and a modicum of storage space. Fuel lived under the seat, which helped lower the centre of gravity of a bike which, at 290kg with fuel, was far heavier than most contemporaries.

Plenty of bikes are far heavier these days (the current top-spec Wing weighs 367kg), and my impression on stepping aboard was very different to that of testers in ’75. The motor started easily, breathing out quietly through its twin exhausts and emitting very little noise from the water-jacketed cylinders in front of my shins.

In other ways, though, the GL felt just as it must have done back then when, with the exception of the Z1, it was the world’s hardest accelerating production bike. It still surged forward with a fair bit of enthusiasm as it headed towards a top speed of about 120mph.

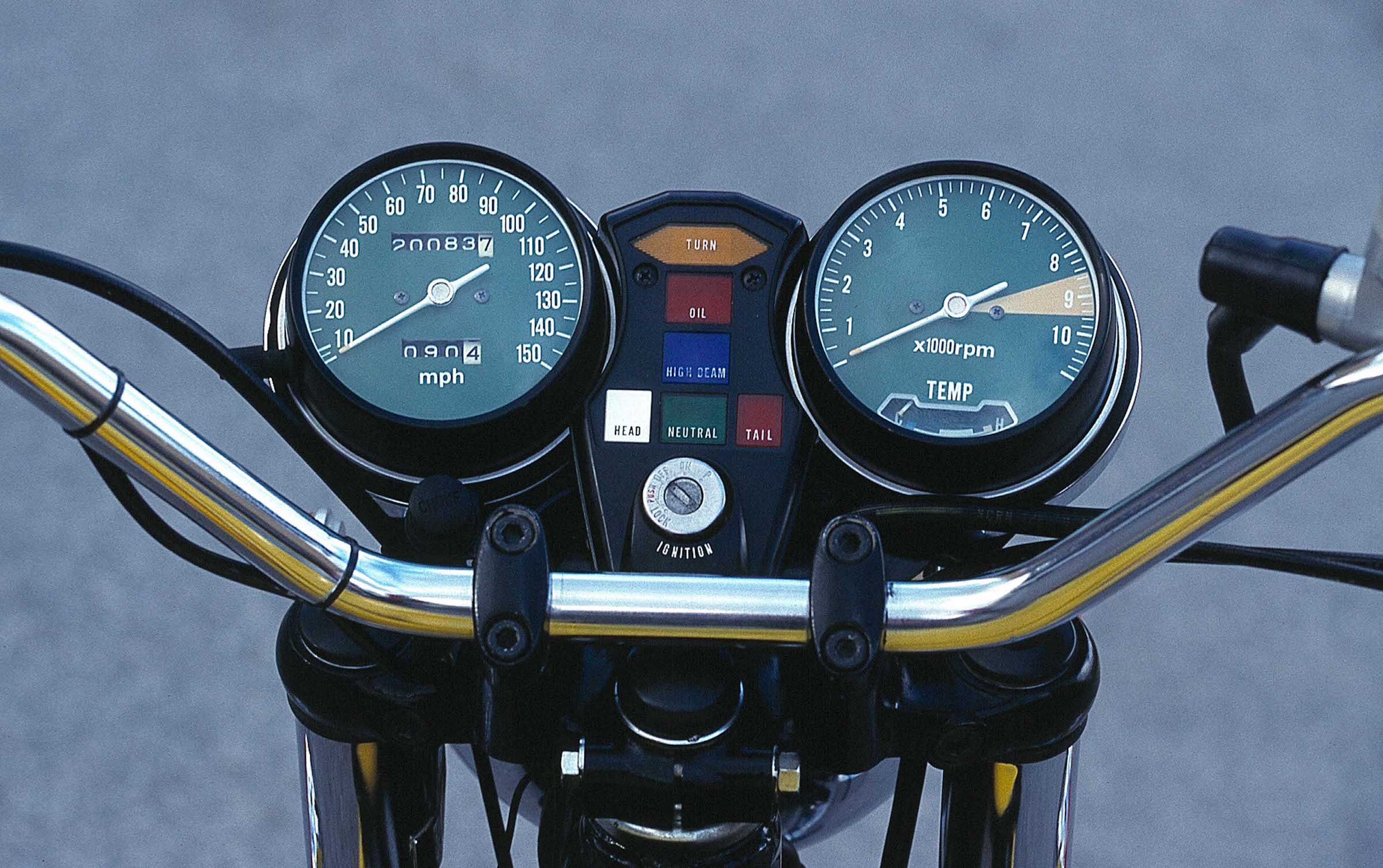

But its greatest attribute was long-legged cruising ability. The GL purred along smoothly and effortlessly at 80mph, and had sufficient midrange torque that it rarely required revving close to the 8500rpm redline. Combined with its light five-speed gearbox (this bike’s liking for false neutrals was typical) and a competent shaft drive system, this gave the impression that the Wing would cruise to the ends of the earth in relaxed comfort.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t the case. The exposed, high-barred riding position was ill-suited to long distances, and the seat soon became a pain. That was less of a drawback that it should have been, because the fuel tank held just 19 litres – good for barely more than 100 miles of fairly hard riding.

Handling was not the Wing’s forte, although its low centre of gravity aided low-speed manoeuvring, and it was less of a handful than I’d expected. Its narrow front forks were fairly firm but the soft shocks began to feel vague and underdamped under moderately hard cornering.

The main problem came when all that weight had to be slowed down in a hurry. The twin front and single disc rear brakes worked fairly well provided the handlebar lever was given a firm squeeze. But using the front brake with the bike banked over even slightly put too much force through the spindly chassis, resulting in a disapproving shake of the head.

The Wing was enjoyable provided I stuck to a fairly gentle pace, though, and its flat-four engine gave it an appealing character. It felt nothing like a tourer; more like the predecessor of the modern breed of giant cruisers like Triumph’s Rocket 3.

The GL1000’s unsuitability for spirited riding was a big factor behind its mixed reception and slow initial sales in Europe. But that was no drawback for many older, more affluent, touring-oriented American riders, who adopted the Wing with enthusiasm and founded rider groups including the GWRRA.

They also soon started modifying and decorating their GLs with accessories, production of which soon grew to become a major industry. First came touring items including fairing, top-box and panniers, followed by custom seats and upgraded suspension units. Before long, you could upgrade your Wing with everything from footboards to a supercharger, plus a vast array of lights and chrome parts.

Honda were slow to produce accessories themselves, but in 1980 they finally released an updated GL1100 plus De Luxe and Interstate models with fairings and luggage. By then, more than 200,000 Gold Wings had been sold worldwide, and the name had become synonymous with long-distance comfort and refinement.

In many ways the testers on both sides of the Atlantic had been right back in 1975. The original, naked GL1000 had many flaws, not least for long-distance travel, but it also had unprecedented potential.

All these years later the original touring legend seems remarkably basic and down-to-earth. Yet there’s still something distinctly special about the Gold Wing.

1975 Honda GL1000 Gold Wing

You’ll love: Long-legged flat-four feel

You’ll curse: When braking into a bend

Buy it because: Old tourer is now a classic cruiser

Condition and price range: Project: £4000 Nice ride: £6000 Showing off: £10,000

Engine: Liquid-cooled sohc flat-four

Capacity: 999cc

Maximum power: 80bhp @ 7500rpm

Weight: 290kg with fluids

Top speed: 120mph

Read more

With a twist of the throttle, the Yamaha RD350LC was a party animal

The Mk2 Honda Legend attracted the wrong kind of attention

Motorised micro scooters are big with collectors

Harley-Davidson and Triumph make adrenaline pump versions to aspire to, Honda made just one big plastic chicken nugget bucket hauler. No good.

I owned one in 1975, I found it handled ok even down B roads if you kept the revs high in 3rd gear and ignored the scraping exhausts.

The only thing missing from so many reviews is the engine’s torque figure. In my opinion it’s super important for cruisers!

Diesel drivers understand what I’m “torquing” about! 😉