Editor’s note: This story was originally published in the Hagerty Drivers Club magazine, for the North American market. Some specifications and timings may differ with the UK market. However, we jumped at the chance to share the story behind one of the greatest engines of all time. James Mills

Human nature is such that even in the darkest of hours, people can still imagine a sunnier future. Thus was it in the depths of World War II, as Luftwaffe bombs rained down on a burning Coventry in Britain’s industrial heartland, that a group of engineers on fire watch with helmets and sand buckets began to plan one of the greatest sports car engines ever to burn petrol. Their creation would remain in production for over half a century, it would be installed in everything from Le Mans winners to army tanks, and it would help revive Britain from the bitter economic malaise that followed its triumph in World War II.

Perhaps most important, it would become forever famous as the gorgeous inline powerplant with the polished aluminium cam covers that purred under the bonnet of the Jaguar E-Type, what motoring journalist Henry N. Manney III dubbed “the greatest crumpet-catcher known to man.”

Origin of the species

Jaguar’s XK six-cylinder engine is a rare instance where exotic aircraft technology successfully executed the leap to a production automobile. World War I aircraft engine designers adopted overhead cams because pushrods between block-mounted cams and distant overhead valves suffered intolerable thermal expansion issues, leading to valve-clearance problems and failures. What they called “tower shafts” linking the crank to the cams proved to be the viable solution – that is, before chains or belts became common drivers of overhead camshafts. Up to the start of hostilities in 1939, such shafts were employed in some exotic and racing car engines as well as V-configured aircraft mills like the famous Rolls-Royce Merlin.

In the teeth of WWII, William Lyons (Sir William after 1956) and his engineering team pondered future engine designs during long hours on fire watch duty at their SS Cars factory in Coventry, which besides repairing aircraft during the war also produced military sidecars and trailers. The team included Walter Hassan, Claude Bailey, and William Heynes, who was well established after stints at Humber and Rootes but who was still subjected to five interviews with the finicky Lyons before being hired as the chief engineer of SS Cars in 1935.

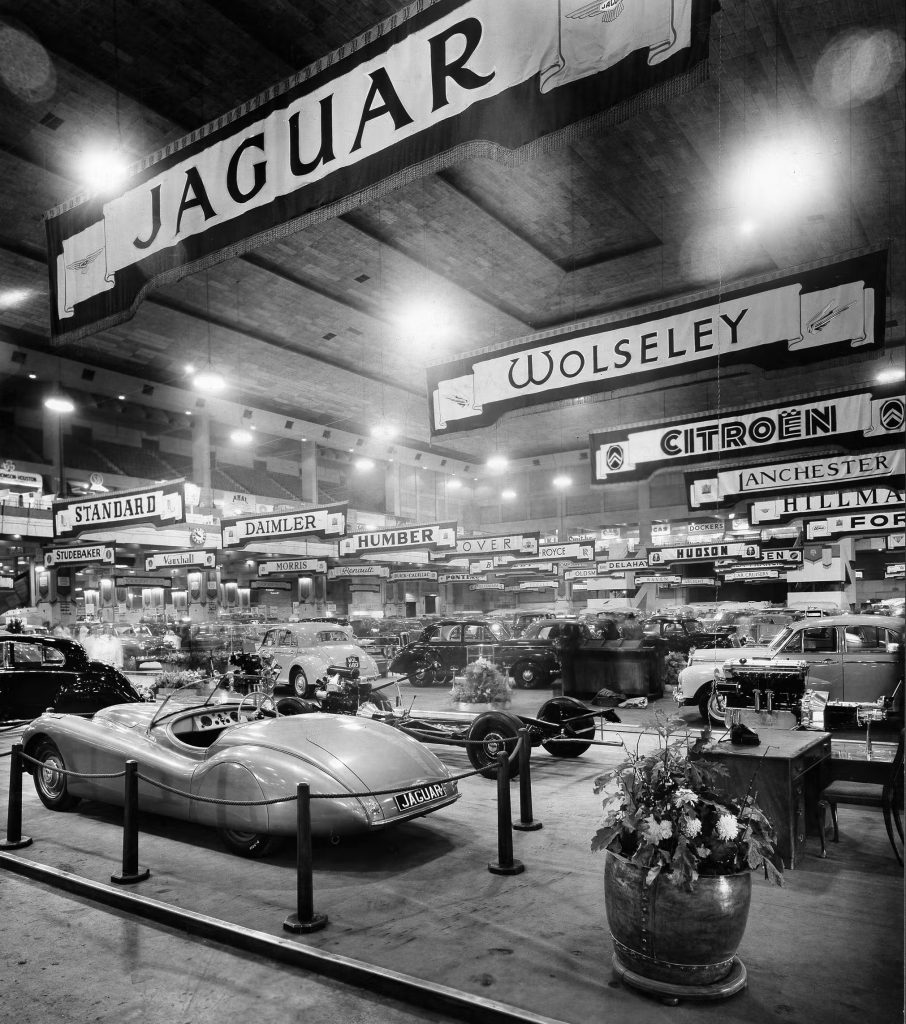

Because the infamous Nazi Schutzstaffel had rendered the SS trademark distasteful by 1945, Lyons rechristened his enterprise Jaguar Cars Limited as the team pondered its role in a world without war. Times were tough all over the globe, but the stiff-upper-lip Brits, desperate for the hard currency won through exports, couldn’t wait to resuscitate their beleaguered car business. In 1947, Britain’s John Cobb became the quickest man on earth, running 400 mph across the Bonneville Salt Flats. And at the 1948 Earls Court Motor Show in London, Jaguar, which hadn’t finished its new saloon in time, instead unveiled a lascivious two-seat roadster that wasn’t supposed to do much except grab people’s attention at the show. Instead, it became the world’s fastest production car powered by what would become one of history’s most remarkable engines.

With America’s overhead-valve V8 revolution a year away and the rest of Europe still licking its war wounds, the new Jaguar XK120 roadster landed with a cymbal crash. Its voluptuous exterior was the perfect antidote to the late-1940s doldrums in England, where shortages and rationing were still in effect. Companies that could export got favourable allocations of raw materials, so Jaguar set its sights on over-sexed, overpaid (but no longer over here) America. And under this sports car’s priapic hood, the 3.4-litre, dual-overhead-cam inline-six glistened like the crown jewels.

Initial goals for Jag’s new engine were top performance, refined manners, a long shelf life, and a delightful appearance. Engines had been made beautiful before by such marques as Bugatti and Duesenberg, but Lyons wanted to build the first ravishing engine to be accessible to a wider audience. At the time, the engines in comparably priced Cadillacs and Lincolns were mere iron lumps. Over a production run spanning six decades, nearly 700,000 of the engines were built in displacements ranging from 2483cc to 4235cc, and the XK6’s distinction as one of history’s most stunning pieces of engineering art proves that Lyons’s lofty aims were exceeded. Added to the engine’s long list of accomplishments is a brilliant competition career, including five outright victories at Le Mans.

Inspiration oven

To organise their thoughts and studies, Lyons’s crew assigned the letter X to stand for experimental, followed by a second letter for each specific design. Four- and six-cylinder configurations were considered but the large-displacement four-cylinder prototypes were deemed too uncouth to serve Jaguar’s upmarket aspirations. Inline-fours lacking balance shafts suffer prodigious shaking forces, while inline-sixes are inherently balanced. (Mitsubishi did solve the four-cylinder vibration issue with counterrotating balance shafts, but not until the mid-1970s.) Sixes also provide a power pulse every 120 degrees of crank rotation versus 180 degrees (half a turn) for fours.

To achieve high volumetric efficiency – expeditious fluid flow in and out of the head – Lyons’ team concluded that large valves residing inside a domed (hemispherical) combustion chamber were essential. By 1947, after 10 alphabet letters had been consumed during experimentation, Jaguar engineers finally agreed on a production design: a 3441cc DOHC engine designated as XK6.

The numerals in the 1948 Jaguar roadster’s XK120 name were code for its top speed. To foil the skeptics, Jaguar engineers dispatched a prototype to Belgium in the spring of 1949. There, a local motor club clocked an unmodified car at 126mph on a straight stretch of highway. With its windscreen replaced by a smaller aero screen, the two-way average topped 132mph. Fitting a tonneau over the passenger seat upped this Jag’s peak velocity to 135mph. The following year, similar XKs averaged 130mph lapping the French track at Montlhéry for an hour and over 100mph for 24 hours. In 1952, an XK120 coupé averaged 100 mph during a full week of endurance running. Decisive actions instead of words proved Jaguar, and Britain, were back in the automotive game.

Jaguar was not the first maker to produce dual-overhead-cam engines. Peugeot racer Georges Boillot won the 1912 and ’13 French Grands Prix with a 7.6-litre DOHC four-cylinder. In road-car use, Sunbeam’s 1926 3.0-litre Super Sports led the way, followed by Duesenberg’s 1928–37 Model J, SJ, and SSJ cars, all powered by DOHC eights with four valves per cylinder.

Core design attributes

Jaguar engineers filled the available engine bay space with a gloriously long inline-six, even though doing so yields a crankshaft more likely to “wind up” (twist about its centreline) under load. A V6 architecture would have solved that issue, but those were ruled out because they required two separate cylinder heads, they weren’t attractive, and they’re not as smooth.

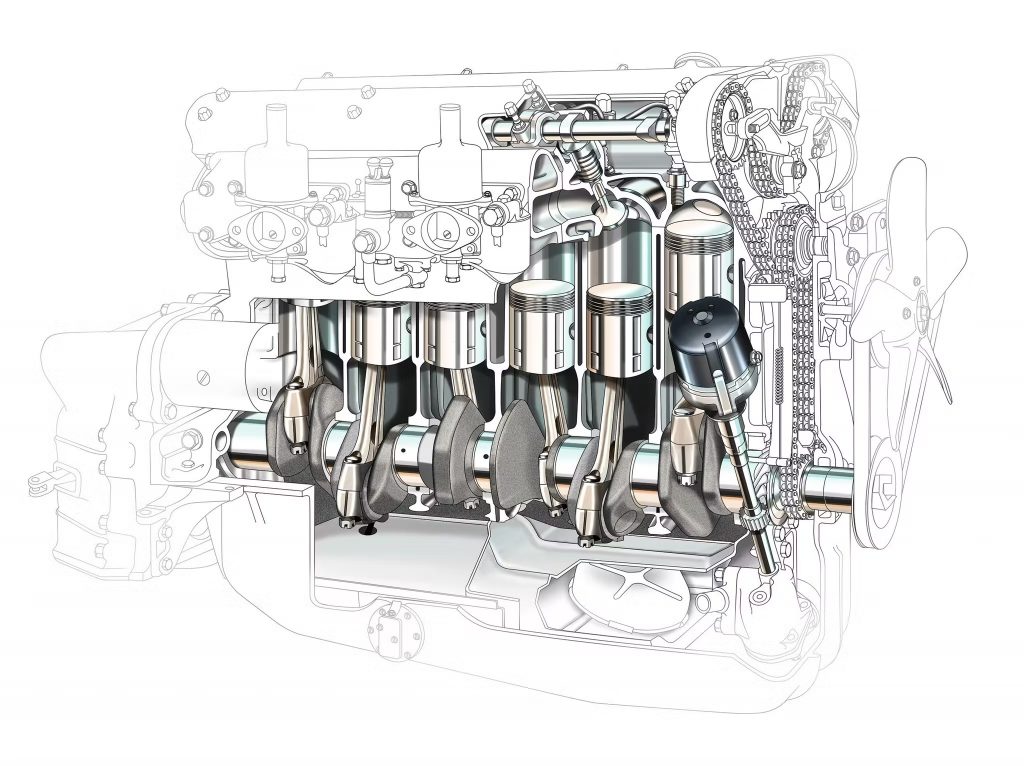

The Jaguar cylinders were arrayed in two sets of three with a wider space in the middle to accommodate extra lateral coolant flow at that location. The cast-iron block extending down to the heat-treated steel crank’s centreline provided seven main bearings for excellent support of the rotating and reciprocating parts. A damper bolted to the crank’s nose diminished residual resonance vibration.

Another attribute provided by a single row of cylinders is that it’s easy to keep the hot (exhaust) side from heating the cool (intake) side, a boon to volumetric efficiency. Such a “cross-flow” design keeps the intake airflow cold and dense to maximise power and torque. Segregating the ports also allowed making the passages entering and leaving the head larger. The alternative, preferred by most makers at the time, was interweaving both manifolds on the same side of an inline engine to simplify plumbing and to use exhaust heat to help vaporise fuel leaving the carburettor.

Using a stroke longer than the bore diameter was common in the 1940s. The small bore minimised overall block length while the long stroke yielded the desired piston displacement. Combining an 83-millimetre bore with a 106-millimetre stroke in the XK6 at the beginning of XK120 production yielded 3441cc, 160 horsepower at 5000rpm, and 195lb ft of torque at 2500rpm.

Chief engineer Heynes, whose later claim to fame was implementing disc brakes for racing, cast the head in aluminium instead of iron to trim roughly 32 kilos off the kerb weight. The XK6’s front timing cover, oil sump, and polished cam covers were also aluminium. Still, the cast-iron block and cast-iron transmission case meant a fully dressed powertrain weight of over 300 kilos.

Aluminium castings did cost significantly more than iron parts, taking them beyond the reach of carmakers not on a performance bent. Durability was a second concern. Iron and aluminium thermal expansion rates are dramatically different, so extra care must be invested in the development of reliable head gaskets.

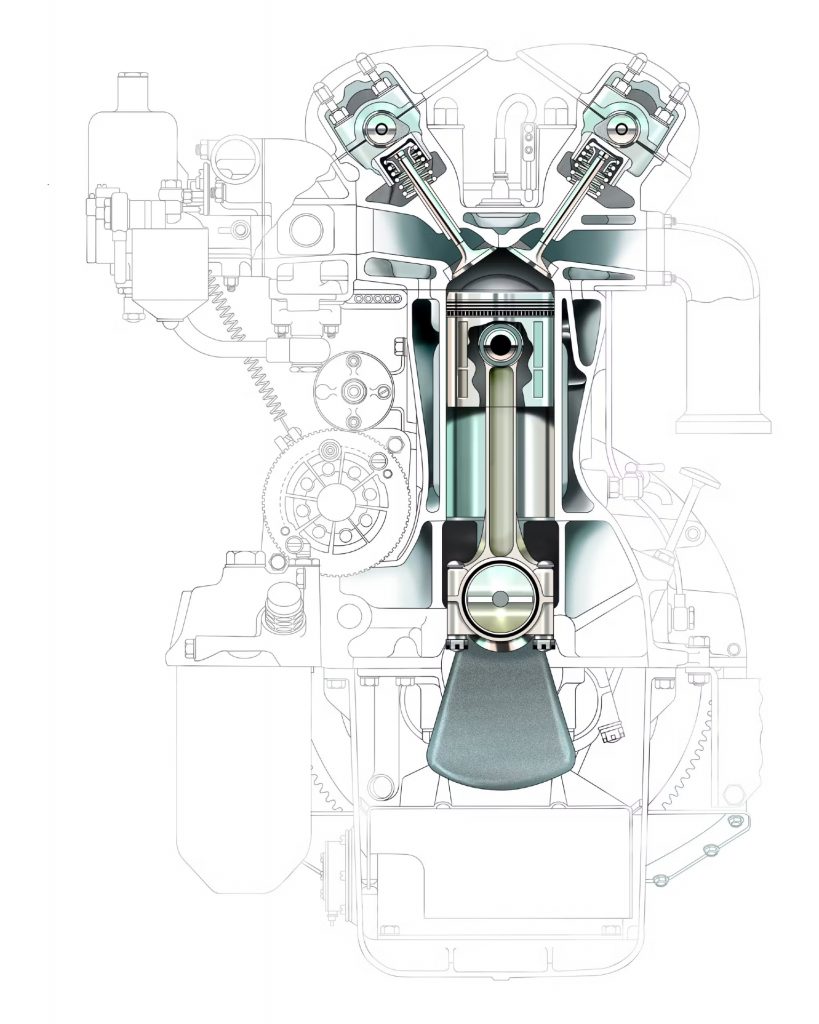

Harry Weslake drew on experience gained developing the indomitable Rolls-Royce Merlin V12 aircraft engine to spread the XK’s valves 70 degrees apart. That wide spacing allowed fitting larger valves in the combustion chamber, thereby enhancing flow in and out of the cylinder. Adding curvature to the intake ports helped the incoming air-fuel mix swirl around the spark plug, which was positioned as near as possible to the centre of the bore.

One of Weslake’s notable contributions to engine development was an innovative testing tool, a flow meter to accurately measure the volume of air moving in and out of the combustion chamber. This in turn allowed for evaluating multiple port and combustion chamber designs before choosing one for production.

Cast-aluminium pistons were fitted with two compression rings and one oil ring. To minimise friction, the wrist pins were a full-floating design, meaning the pin was free to slide inside both the connecting rod and the piston. (The cheaper alternative was a press fit in the rod to avoid the snap rings in the pistons that keep the wrist pins from rubbing against the cylinder walls.) A smooth dome atop each piston set the compression ratio; most markets used a ratio of 8.0:1 at the beginning of production.

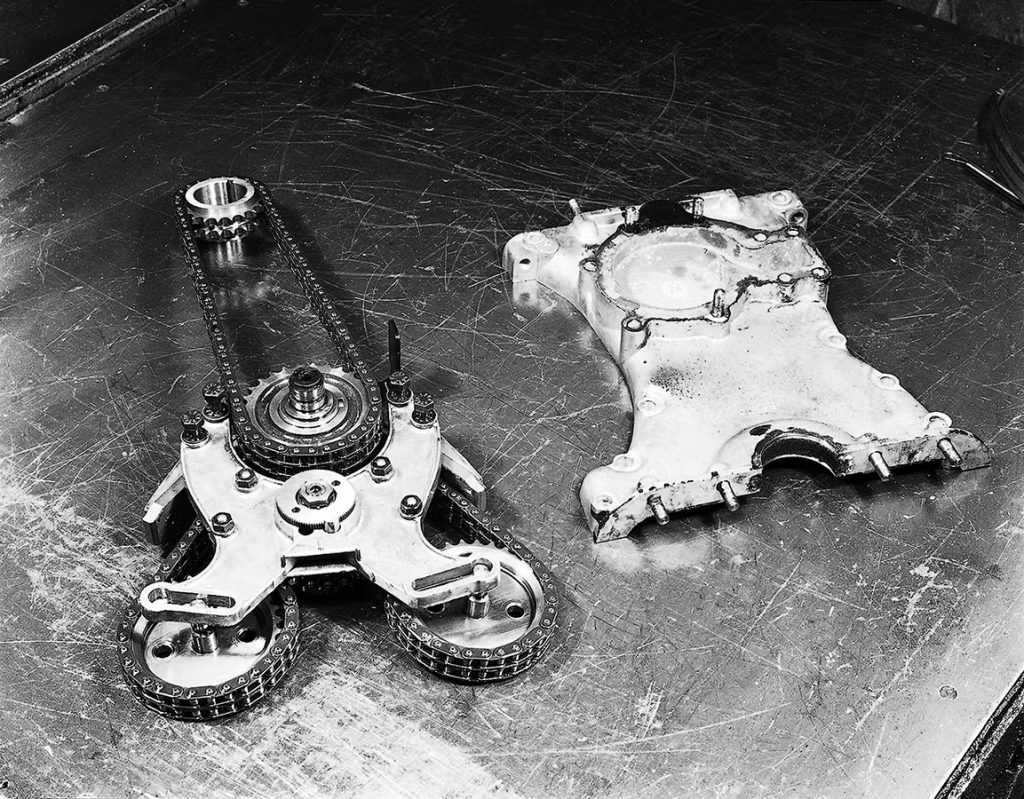

Inverted bucket tappets containing shims to adjust valve lash were fitted between each valve stem and its cam lobe. A two-stage drive spun the overhead cams: one chain from the crank nose up to an intermediate sprocket with a second chain linking the intermediate sprocket to the two cam sprockets. These roller chains were double wide for long life.

Ready to rumble with stylish twin SU side-draught carburettors and Lucas ignition, the XK6 engine alone weighed about 250kg, while a base XK120 roadster’s kerb weight was listed at 1320kg thanks to the aluminium bodywork fitted to the first 200 cars. Acceleration from 0 to 60 mph took about 10 seconds.

Variations on the XK6 theme

Although the XK120 roadster was a sensational means of introducing Jaguar’s notable technological stride, it was merely the low-volume start of spreading dual overhead cams, aluminium engine castings, and a stunning engine-bay appearance throughout the company’s mainstream models. Jaguar’s Mark VII four-door saloon arrived in 1951 to share 150 and 160bhp versions of the 3.4-litre XK6.

A low-volume (only 53 built over three model years) racing-oriented XK120C enjoyed several notable upgrades. This speedster with its aluminium body over a steel-tube frame had a wheelbase 6 inches shorter, no top, and only one door. Wilder valve timing, larger valves, more efficient porting, higher compression, and larger carburettors raised output to 200 horsepower at 5800rpm. The XK120M (modified) edition that arrived in 1952 contained suspension upgrades and knock-off wire wheels. A two-seat convertible with wind-up windows and more elaborate folding top – known as a drophead coupé – came in 1953, followed by the D-Type sports racer in ’54, powered by a 250bhp version of the XK6 and benefiting from a new cylinder head and three carburettors. Only a handful of Ms were built, with a price roughly triple that of a standard XK120.

In the 1950s, Jaguar sports cars were all-conquering at Le Mans, with overall victories in 1951 (XK120C), ’53 (C-Type), and ’55–57 (D-Types). In the 1957 24-hour race, five of the top six cars were D-Types campaigned by privateers.

In ensuing model years, Jaguar nurtured its DOHC six like a loving parent. The 1955 XK140 brought notable power and torque gains from the same 3441cc, raising horsepower to 190 at 5500rpm and torque to 210lb ft at 2500rpm. To extend the model range downward, a smaller version of the XK6 arrived in 1956 in a less expensive saloon called the 2.4 Six. This 2483cc DOHC engine with a shorter stroke and deck height produced 112 horsepower at 5750rpm.

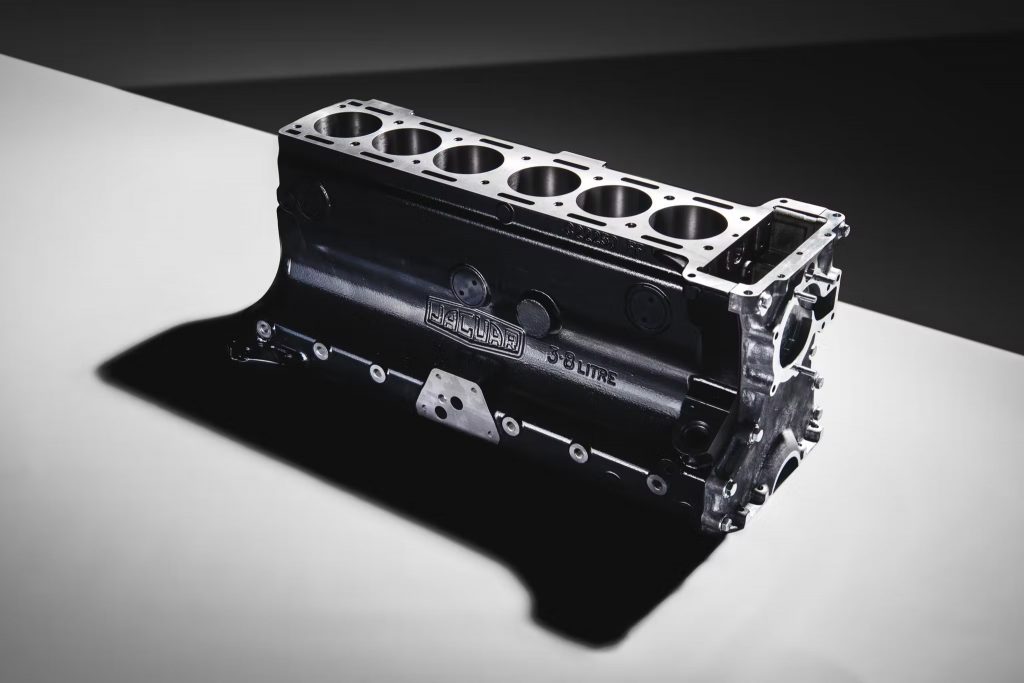

Fresh sheetmetal and more power came in the 1958 XK150 two-seaters, which offered 210 horses at 5500rpm. A new 1959 Mark IX saloon was equipped with a 3781cc six with a bore 4 millimetres larger and 220 horsepower. The 3.8-litre engine was available in the Jag sports cars in three forms: 220 horsepower with two SU carburettors, and 250 or 265 horsepower with higher compression and three side-draught carbs. To accommodate larger bores, the cylinder walls were slotted for coolant flow and wet liners were pressed in to provide sealing.

Because this engine was failure-prone, Jaguar recently began offering new 3.8-litre blocks through its service channels for about £15,000. That’s a lot of cash, but it does help keep classic Jaguars on the road.

The company’s sensational E-Type arrived halfway through the 1961 model year in coupé and roadster form, with the triple-carb 3.8-litre six delivering 265 horsepower at 5500rpm and 260lb ft of torque at 4000rpm. For 1965, Jaguar shuffled cylinder spacing in a new block to accommodate a bore increase, from 87.0 millimetres to 92.1 millimetres, raising displacement to a husky 4235cc.

In contrast to the original layout of two sets of three cylinders with a wider space between cylinders three and four for coolant flow, the bores were now evenly spaced. A new crank had repositioned throws and mains. Oddly, the cylinder head was not reconfigured, resulting in a small misalignment between each combustion chamber and its corresponding bore. Because the diameter of the combustion chamber was smaller than the bore diameter, the only negative consequence was a slight sacrifice in peak power.

Maximum output in the 4.2 remained the same as the 3.8 – 265 horsepower – but at a slightly lower 5400rpm. The 4.2’s torque swelled to 283lb ft at 4000 rpm, leading to 4.2 owners claiming better low-end torque while 3.8 owners say their engines are more eager to rev. In 1969, engineers dropped one carburettor and switched from SUs to Zenith-Stromberg units, which were better able to meet America’s tightening emissions standards. That lowered the engine’s output to 246 horsepower and 263lb ft of torque. Making amends, Jaguar introduced an all-new 5.3-litre V12 in 1971 rated at 250 horses and 283lb ft at 3500 rpm (both ratings now compliant with the new SAE net power-measuring standards).

Though the venerable XK6 was phased out of E-Types in 1971, it did continue powering Jaguar XJ-6 saloons. In 1978, the addition of Bosch L-Jetronic fuel injection kept this classic engine gainfully employed through the 1987 model year.

Endgame

Without retiring its beloved XK6, Jaguar introduced a clean-sheet AJ6 (for “Advanced Jaguar 6”) engine in 1984. While the rest of the world was migrating toward tidy V6s, the Coventry crew stuck by what it knew best, investing more than £30 million and a decade of R&D into a new 3590cc inline-six, only the third all-new engine that Jaguar had ever produced. The AJ6 brought aluminium block and head components, dry steel cylinder sleeves, dual overhead cams opening four valves per cylinder, pent roof–shaped combustion chambers, electronic fuel injection, and a cost-saving cast-iron crankshaft. This new 195kg six arrived in downsized 1988 XJ6 saloons with 181 horsepower at 4750 rpm and 221lb ft of torque at 3750rpm. For European markets with less stringent emissions standards, the AJ6 delivered a more impressive 225 horsepower and 240lb ft of torque.

Meanwhile, the XK6 remained in service for Britain’s Scorpion light tanks and Scimitar armoured reconnaissance vehicles. XJ6s not imported to the United States offered 2.8- and 3.4-litre versions of the engine from the late 1960s through the mid-1980s.

The final hurrah was a 4.2-litre XK6 engine Jaguar supplied to power the very last 1992 Daimler Sovereign limousine – in essence, the poor monarch’s Rolls-Royce Phantom. Properly cared for versions of these swoop-tailed limos are still in service around the globe. (See them on Netflix’s The Crown docudrama series.)

Plenty of specialists in England and elsewhere are busy keeping XK6 engines in fine fettle, and British tuners Eagle and Vicarage have continued serving E-Type customers with 4.7-litre versions of the XK6 providing 370 or more horsepower.

What Jaguar’s XK6 proves is that thoughtful updates – what the British call their “make do and mend” spirit – can keep a brilliant engine design thriving for half a century. Thus, what initially seemed like a risky undertaking for a group of engineers trying to figure out how their small company would make its way after the war, soon made Jaguar Britain’s most adored carmaker.

Read more

How will you do in our Jaguar centenary quiz?

Concept Cars That Never Made The Cut: Jaguar F-Type X600

Cats in disguise: 10 Italian cars that were actually a Jaguar