If you were looking for a story on which to pitch a Formula One film project, the story of Connew would appear to be too good to be true. A bunch of beer-drinking friends wonder how hard it can be to build your own F1 car and get to the start line. Despite having no experience, before you know it the likely lads have rented a lock-up, rolled up their sleeves and set to work.

The 1970s was Formula 1’s ‘Kit Car Era’. The widening spread of availability of Cosworth’s DFV V8 engine and Hewland’s DG gearbox provided the backbone to a growing domination of the category by British constructors. Freed from the exorbitant costs of such development and production they were instead able to invest the time and money saved into the honing of their chassis and, more importantly, the harnessing of the most recent performance parameter: aerodynamics. Enzo Ferrari, his foundry huffing and puffing to keep up, sniffily called them garagisti. He didn’t know the half – barely a quarter – of it.

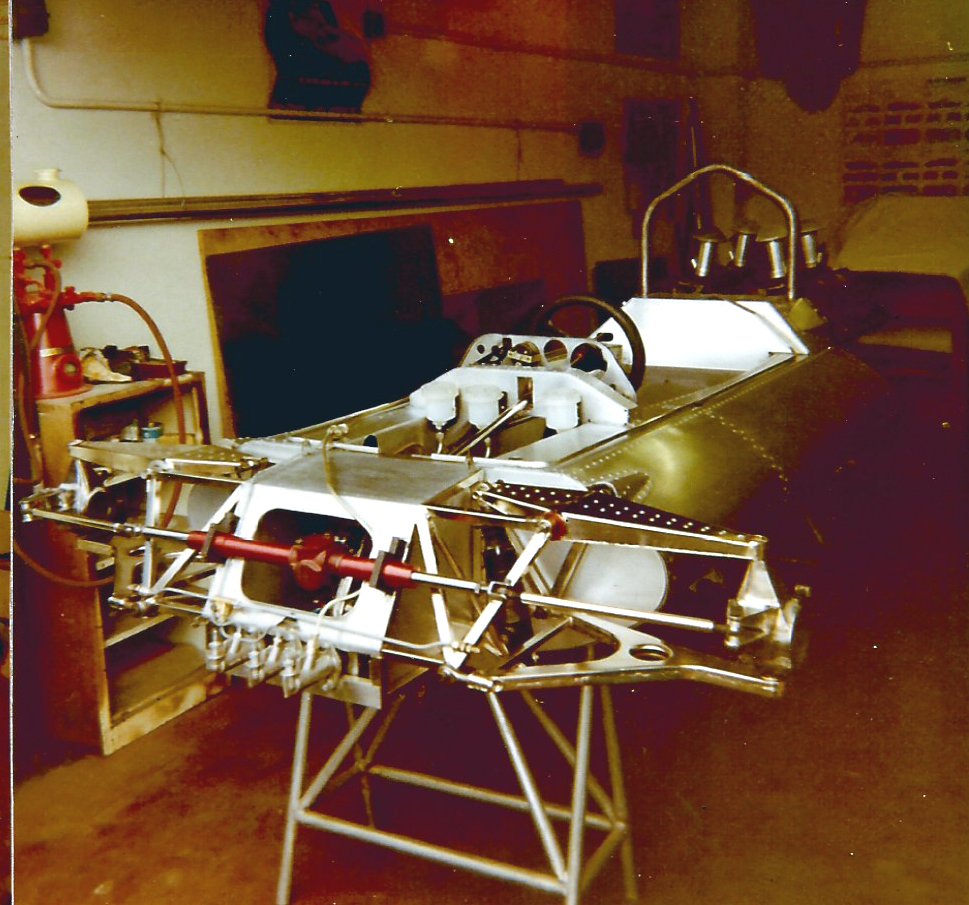

For in an East London lock-up barely bigger than the car therein were four young men working three nights a week and at weekends to painstakingly turn – there was more pain than steak – their F1 dream into reality.

The leader, Peter Connew, was a 23-year-old designer and draughtsman whose head had been turned by a visit to Monza in 1969. That Italian Grand Prix was a humdinger – the top four were separated by less than two-tenths at the chequered flag – but it left Peter Connew cold nevertheless. No, it was the sound and the engineering that fired up this maker of record players. He would have a new job within months – at John Surtees’ racing team in Edenbridge, Kent, working on this former world champion’s stopgap F1 McLaren and its nascent replacement, the eponymous TS7. Connew had started at the top and would learn on the hoof. With no knowledge of racing’s lower formulae, it would have to be F1 or nothing thereafter.

Needless to say, Connew couldn’t manage all this on his own, so he called on the help of friends. There was Roger Doran, a meticulous joiner/shopfitter, whose father Ron, aka ‘Daddy D’, was an expert welder; Ron Olive, a competent engineer whose union sympathies would cause him to leave when his broaching of paid overtime was drowned by laughter; and Barry Boor, Connew’s distant (socially rather than geographically) cousin, a recently qualified woodwork teacher taken to working at a funeral directors to make ends meet while also having access to a telephone. Oh, and there were a couple of likely lads from the Elephant & Castle, nicknamed ‘Pinky’ and ‘Perky’. (I am not telling porkies, I promise.)

“Peter’s father and my mother were siblings,” Boor tells Hagerty. “We lived above my mum’s grandparents in Bow, whereas Peter’s family was in Dagenham. We saw quite a lot of each other when we were of junior school age, but after that I rarely saw him.

“His father owned a turquoise Standard Pennant and our families had piled into it and gone to Brands Hatch in August 1960 for the opening of its Grand Prix loop. I had been into motor racing since I was nine, but, from that day until that trip to Monza, I doubt that Peter had any interest in it whatsoever.

“So to be then given the opportunity [just after Christmas 1970] by him to become involved in F1 was amazing. And surprising. He has never lacked confidence.”

The design for the homebuilt F1 car had begun in March 1970 and its construction started that September, with a view to having it ready for the 1971 Monaco GP: a target far too ambitious. Connew, who had left Surtees, was making parts during his lunch break at a small engineering firm – and the anticipated sponsorship had not yet arrived.

Such naïveté was what kept them going while at the same time holding them back.

Boor continues: “Peter used to do bits and pieces for £20 here, £30 there, and literally he would say, ‘Right, I’ve got some money today and so I’ll go and buy some fibreglass.’ Or resin. Or tubing. That’s why the whole thing took so long; we didn’t finish the car until Easter 1972.

“We had a few drivers come along to see it – Gerry Birrell and Howden Ganley – and they were encouraging. Looking back, though, we must have been crazy to even attempt it. We just felt that we would get it all together. One day.”

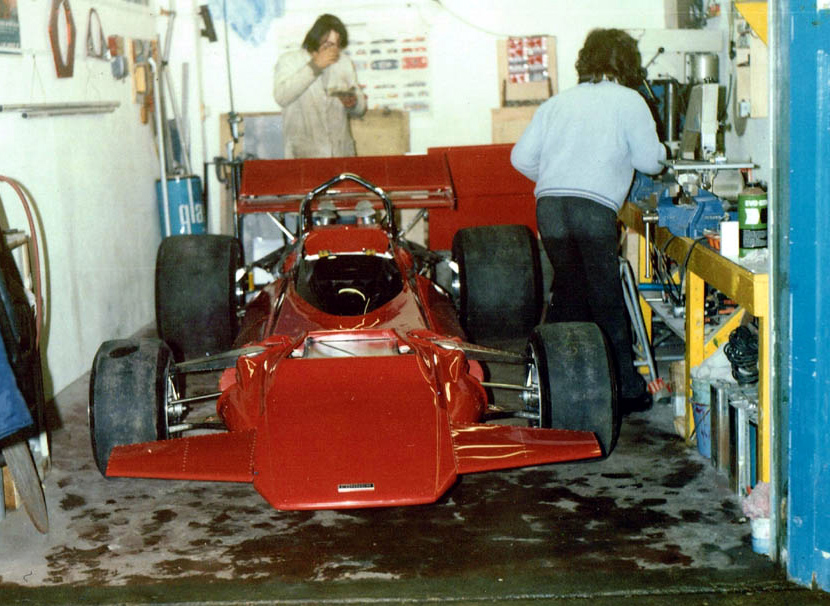

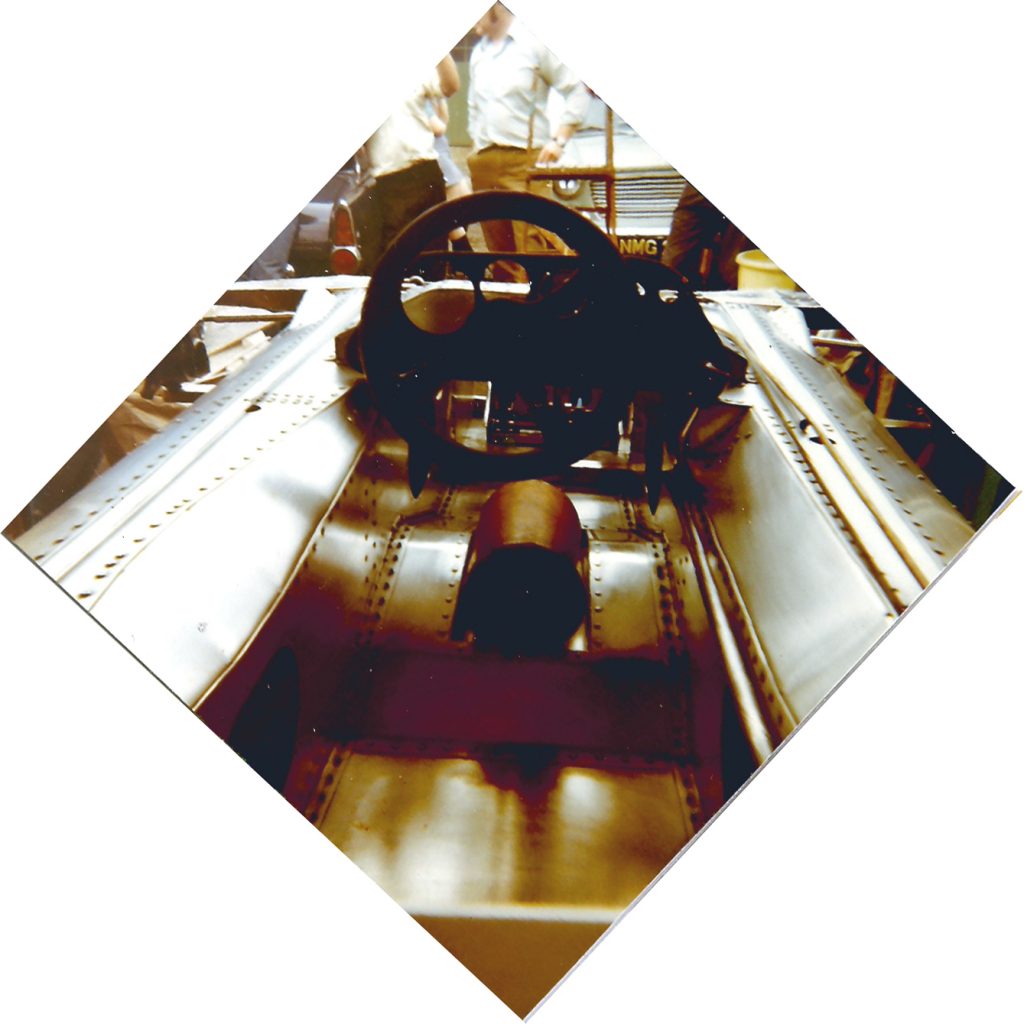

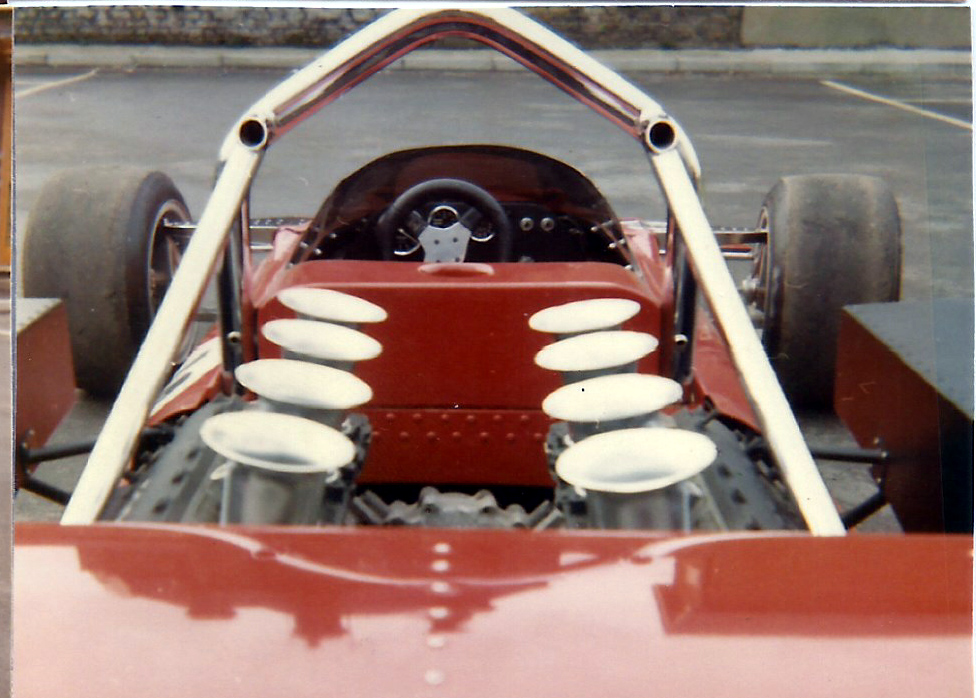

On borrowed tyres and wheels, and fitted with genuine Cosworth DFV and Hewland gearbox (albeit minus their internals), it was prepped in readiness for the 1972 Racing Car Show – held in January on a Townsend Thoresen ferry moored on the Thames! (By which time a monocoque made of thicker aluminium was under construction because of a regulation change.) Fans and insiders were as much impressed by the quality of the car’s build as they were amazed by the story and quality of the building behind it. For this was no bodge job. There were neat touches, too. Its nose carried a radiator inclined just five degrees from horizontal, fed from its underside. This would work well. Its rear suspension incorporated a degree of à la mode rising-rate springing – which allows for softer springing without comprising body control and aerodynamic attitude at the extremes of acceleration and braking – and eschewed radius rods locating it fore and aft. This would not be as successful.

A feelgood factor was beginning to build and help was forthcoming: from Ford (a free quick steering rack off an Escort) and Firestone (tyres); from Girling (brakes) and Armstrong (dampers); and from renowned fabricator Maurice Gomm, who ‘forgot’ to invoice for the rolling of the monocoque’s curved outer skins.

“We had no money,” says Boor. “We were not well known. But people liked that. Phil Kerr at McLaren was brilliant to us; he let Peter take away a [used] DFV for just £1000, on the understanding that the rest would be paid later.”

PC1 was coming together. All it needed now was a driver. Enter François Migault. A winner of the prestigious find-a-driver Volant Shell prize, two solid seasons of French Formula 3 – he finished fourth in the championships of 1971 and 1972 – and a couple of promising outings in European Formula 2 had persuaded this man from Le Mans and his backers that he was ready for the big league.

“Possibly he had been warned about what he was going to find,” says Boor. “But he was young, and to have an F1 car that was going to be his was exciting. That it was being made in a tiny lock-up was neither here nor there. F1 was his dream, too. A lovely bloke, he mucked in and wasn’t afraid to get his hands dirty.”

A deal was struck – reputedly £40,000 for five GPs, starting with the French at Clermont-Ferrand in July – and the red car would wear a broad yellow stripe and a Connew-Darnval badge on its nose in accommodation and recognition of Migault’s sponsors and supporters.

“It was not a huge amount of money, but it was enough for Peter to put down a deposit on that engine, and buy a gearbox, eight wheels and the [fuel] bag tanks,” says Boor. “Once we had those it was just a matter of putting it all together.

“Initially we only had one lock-up, but Peter managed to get another unit, three or four doors down the yard; we moved the big lathe and most of the machinery into there. Prior to that the car had been on stands, with no wheels fitted. Once it was on its wheels you had to step over them to get around. It really was very tight.”

By Easter the team was operating full-time – for £30 a week. It not only completed the build – almost shaking down the lock-up when the DFV ran for the first time, at 10pm – but also it had fitted out the bare Ford truck driven to England by the eager Migault.

The truck broke down in France en route to Clermont-Ferrand. Eventually PC1 was hauled as far as the Le Mans Bugatti circuit, where the local hero shook it down – until Connew noticed bent suspension; incorrectly loaded, it had been allowed to heave and bump in transit. That naïveté again. Scratch the French GP.

The British GP at Brands Hatch saw PC1 squat and scrape on increasingly soggy springs during the first day of practice. Rushed back to base at Chadwell Heath on the Romford Road, repairs took 40 hours straight, and a police escort was arranged for race morning – until a cracked rear upright was spotted as the sun came up. Scratch the British GP. But at least Migault had in theory qualified. Despite restricting himself to a lowly 9000rpm – “break it, and we were finished” – he had lapped within 8.1sec of Jacky Ickx’s pole-sitting Ferrari.

The team didn’t have an official entry for the German GP but its breezy driver reckoned that he could schmooze his way in. He got as far as scrutineering before it kicked off and the team was kicked out. Scratch the German GP. In truth, this was probably a mercy because the undulating Nürburgring was notoriously hard on suspensions, plus Migault had no knowledge of its 14-mile lap.

A harsh lesson learnt, an entry was confirmed prior to the Austrian GP. The team felt part of the F1 circus at last – though its popularity dipped when the oil tank split and dumped lube around the circuit during practice. Its car, however, was running better now that a rival had indicated how its fuel system had been incorrectly plumbed. Migault lapped within 6sec of Emerson Fittipaldi’s pole-sitting Lotus.

People, says Boor, were beginning to take notice. “Somebody who had been timing the drivers through the second corner, a fast, sweeping right-hander, came to see us to say that only [reigning world champion] Jackie Stewart had been faster than François. I thought, ‘Yeah, maybe.’ But I do reckon that François was pretty good. It’s just that he was losing chunks of time because of our rev limit.”

True, had not Le Mans 24 Hours winner Henri Pescarolo crashed Frank Williams’ privateer March in practice, the Connew would not have started. But it did make the grid. And it would survive until lap 22 – earning much-needed prize money along the way. An aluminium plate locating part of the rear suspension eventually split, but despite the scary moment that this caused him, Migault emerged unharmed and euphoric. The team was buoyant, too – before its long journey home at least.

“We had a French Roger driving the truck,” says Boor. “A nasty piece of work, he had a really bad scar on one of his legs; he said he’d crashed while racing. Anyway, our Roger, running a short fuse, did not get on with him at all. We were running out of diesel yet French Roger was determined to make it into France, because there he could pay for fuel using a book of vouchers given to him by Shell. If Peter and I had not been sat between them, the Rogers would have had a fight.

“We made it, just, late at night, and French Roger disappeared to find himself some feminine company. We stayed with the truck: Roger slept in the cab; Peter slept in the racing car; and I slept on the floor between its wheels.” Ah, the glamour.

The promise of another much-needed payday persuaded the team to enter the Rothmans [$]50,000 at Brands Hatch, a strange Formule Libre affair in August; there were only seven F1 cars on its otherwise packed grid. Sadly PC1 began emitting smoke during practice: a piston slapping in its bore had cracked its cylinder’s liner. Experienced ears had heard it going wrong for several laps. That naïveté again. Scratch the Rothmans 50,000. Scratch Migault, too. Determined to find his F1 fix elsewhere, he bid au revoir.

Enter David Purley. He paid £600 to have the engine rebuilt and the car resprayed in the colours of his father’s Lec refrigeration business – blue with red stripe – and it was entered for October’s John Player Trophy, also at Brands Hatch. Purley qualified 10sec slower than Fittipaldi – and tellingly a half-second slower than Migault’s July best. (The latter had used some of his ‘Connew’ money to hire a March for this race – and crashed it on his first flying lap.)

A recent scare with a stuck throttle persuaded Purley of the need for an ignition kill switch on the steering wheel. Fitted the night before the race, one of its wires broke on the formation lap and the car coasted to a halt. The F1 dream was over. The engine was sold and the outstanding balance to McLaren paid: £2550 – minus £100 for honesty.

Brands Hatch’s go-ahead and understanding promoter John Webb paid the team £600 to keep it afloat, and the car was converted to accept a cheaper, still powerful but much heavier 5-litre Chevrolet V8: PC2 would contest one Formula 5000 race in 1973. (It should have been two but an oil leak prevented Swiss amateur driver Pierre Soukry from starting at Mallory Park in July.) With the experienced Tony Trimmer at its wheel at Brands Hatch in October, a top broke off a shock absorber, sending its spring far into the woods and the car hard into the barriers. A front wheel folded back and whacked the monocoque. The F5000 ‘dream’ was over, too. Connew went back to repairing Jaguars and Boor returned to teaching.

It was hardly a Hollywood ending. “But it wasn’t a failure,” says Boor. “Peter’s plan was to build an F1 car and race it in a GP. And that’s exactly what we did.”

Here’s the closing scene: our hero Migault chases the jostling pack through the dust, up the hill and over the crest towards the first sweeping turn of the Österreichring…

Read more

These boots were made for racing

50 years later, Ford’s Transit Supervan is still outrageous

The epic challenge of building a Tyrrell P34 six-wheel F1 continuation car

youngsters look amazed when I tell the story of building ‘your own’ f1 car. now please do the story of the Canadian driver who took the twincam ford out of his lotus cortina and put it in his lotus 18 formula junior and qualified for the glen gp

You preface the Connew story with the comment that it would make a fine F1 film project and you’re absolutely right. I guess the appeal might be limited as far as the financially necessary general-public audience is concerned, so maybe a drama-documentary for television might be the answer. Does Hagerty number any television producers amongst its customers? I’d hope so.

On another matter: your on-going stream of emails relating to motoring matters is a delight. Many thanks for the entertainment.

Great story