The period immediately following the Second World War was a strange time in Great Britain. The national mood was one of optimism forged from the defeat of fascism, but balanced with the necessary austerity of a country whose economy had been stretched to breaking point by the demands of the conflict. The world – and Britain’s place in it – had irrevocably changed; lacking the clarity of purpose and defined narrative of defeating Nazism, independence movements sprung up throughout the Empire, and at home some began to question what was next for the country.

In the motor industry, investment in new engineering in the late 1940s was initially limited and in both the mass-market and motor sport, pre-war technology had to be used. That meant that when Grand Prix racing resumed in 1947, the Italians made the most of the lack of German competition and immediately dominated, the Alfa Romeo 158 Alfettas winning every race they started. This success by a previous Axis power sat badly with the British, and especially Raymond Mays, whose ERA just didn’t give him the performance he required, despite pushing it as hard as it would go.

Mays and others saw motor sport as aid to revitalising the British motor industry and as a way to enhance national cohesion and pride. Whilst others like John Cobb and Goldie Gardner flew the flag by returning to setting speed records, May’s idea was more ambitious: to create a world-beating British Formula One car that would dominate the sport and showcase British engineering talent.

Using his considerable influence, by 1946 Mays had persuaded no fewer than 40 companies to back his British Motor Racing Research Trust to finance and develop the vehicle, which was to be run under the evocative name of British Racing Motors, or BRM.

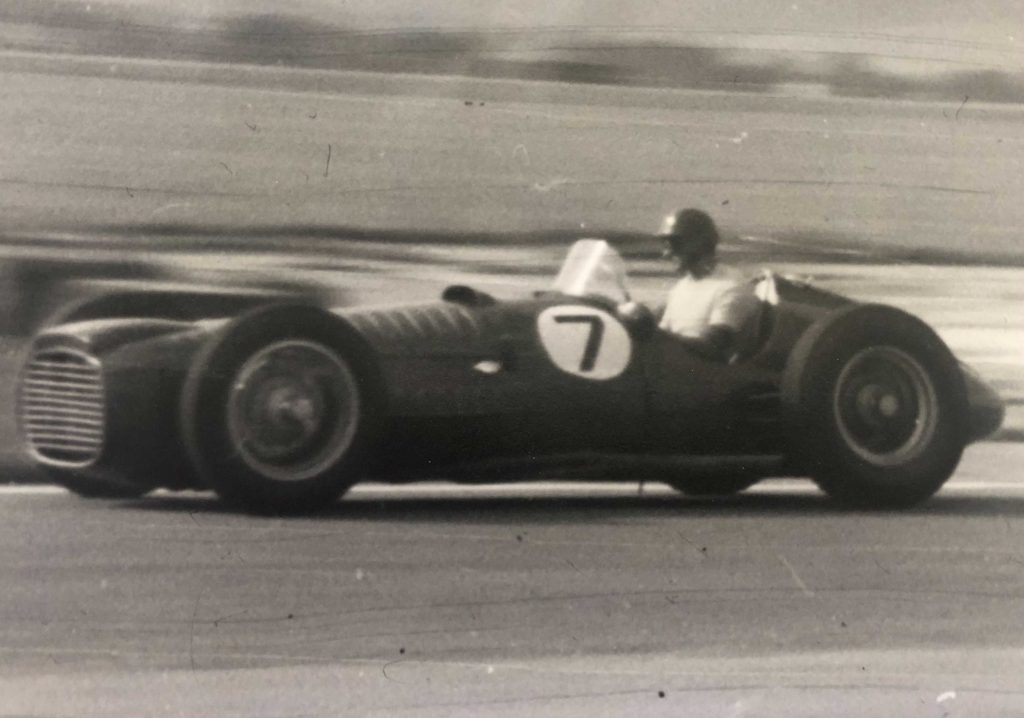

Supported by other British companies and donations from individuals, BRM, headed by chief designer Peter Berthon, May’s old colleague from ERA, set up shop in Bourne, Lincolnshire and started the build. The design was very ambitious: a front-engined, 1496cc, double overhead camshaft V16 fed by a complex centrifugal supercharger built by Rolls-Royce running at 70psi, an unheard-of pressure for a car. Other innovations included (in 1951) disc brakes, the first time these had been used in road racing, five-speed transmission and oleo-pneumatic strut front suspension.

Meanwhile, the car’s publicity campaign swung into action, and soon the home press were clamouring for news of the car until, by the time it was unveiled at a cold Folkingham Aerodrome in December 1949, it seemed that everyone in Britain knew the name of what was officially designated the BRM Type 15.

“Obviously it’s a new motor car,” Mays said to the press at the launch, “and there’s quite a lot of development work to do on it, but we have high hopes… that this car will uphold British prestige and so do a great amount of good for the country.”

The initial demonstration went well, with the extraordinary sound of P15/1 revving to over 12,000rpm as Mays tracked it around the airfield, but the development work he mentioned was causing the team some acute headaches. Simply capturing that extraordinary power and transmitting it through the skinny period tyres onto the road in any meaningful sense was proving to be very difficult, and the planned debut at the 1950 Silverstone British Grand Prix was cancelled.

Even by the time of the next planned outing, the Daily Express Trophy race at Silverstone on August 26th, Mays felt it was not ready. Meanwhile, his investors and supporters were becoming restless, and the decision was made to enter the car so late that it missed the practice sessions. Undaunted, French driver Raymond Sommer duly lined up on the back of the grid for the start of the second heat, and when the flag dropped… the car jolted, then stopped. The extraordinary power of the engine had broken the driveshafts.

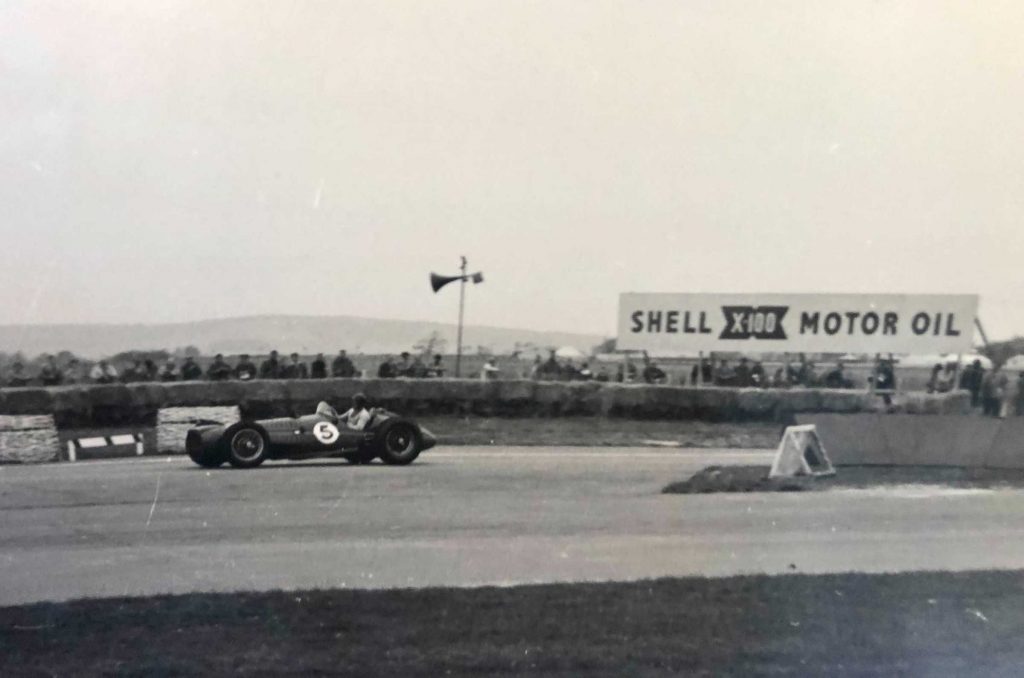

A month later, BRM tried again, this time at Goodwood. The result was a total success, Reg Parnell taking victory in both the Woodcote Cup and Goodwood Trophy races in front of a delighted crowd, but it was to be a short-lived respite for Mays and his team. After Goodwood, reliability issues once again became a recurring theme for the car: of the next seven outings for P15/1, the car finished just one race, the 1951 Silverstone Grand Prix, in a disappointing fifth.

The writing was on the wall. In 1952, BRM was sold to Sir Alfred Owens. But the car was not dead: a huge amount of development work was invested in the car, and by mid-1952 it was substantially rebuilt. By the 1953 season, it was finally reliable and competitive.

Unfortunately for BRM, the Formula One rules had been changed to match F2 rules (2 litre unsupercharged or 750cc blown) leaving the V16 no place on the grid, and the car had to be entered in a series of other races including those at Albi, Goodwood and various Formula Libre competitions. Driven by men including Fangio and Ken Wharton, two drivers whose style suited the brutish force of the car, the V16 nevertheless showed its ability during this period, dominating almost every race it entered.

The BRM P15 V16 was a polarising car. Even the drivers had vastly different opinions: Stirling Moss refused to drive it and Hawthorn hated it, but Fangio called it “the most fantastic car I ever drove – the most incredible challenge in every way.”

Today, it is an unmistakable milestone in British racing history: an instantly recognisable car with a trademark roar that is unlike anything else on the track. Fortunately, thanks to the BRM V16 Continuation cars, that sound is once again being heard more regularly, as we recently experienced at the 2021 Goodwood Revival.

Whilst there, Hagerty was also very privileged to see the car that started it all: BRM P15/1, now in the care of the Beaulieu National Motor Museum. Watch our interview with Beaulieu’s Chief Engineer Doug Hill, about the car and find how it is maintained.

With thanks to Doug Hill and the National Motor Museum, Beaulieu for their help in researching this article.

Read more

New BRM V16 F1 continuation cars will restore the roar

Freeze Frame: British victor for the first Monaco Grand Prix

Raymond Sommer: The Unknown Great