“A lot of the bike commissions I’ve had over the years have usually taken place at one or two in the morning after a few drinks at a motorcycle event. It’s handshakes and hugs and then you wake up in the morning with a slight hangover and follow up with a little email, saying ‘Hey I’ll get in touch next week when we’re all back to normal.’ In our industry, trade shows are at events – it’s great fun but you are there to do business. That’s how I met the big boss of Yamaha’s Yard Built Program and got the contract to build the XV950, the bike that got away.

It was 2014, and Yamaha had just launched the European side of the “Yamaha Yard Built” programme that started in the USA a couple years prior, where they give custom builders a bike from their Sport Heritage range to put their spin on it. Part of the deal was that you have to design and develop a couple of unique parts for that model of bike, it could be a set of hand or foot controls, an exhaust system or a set of engine covers, that can be manufactured and marketed to the public afterwards so that they can build and customise the same model of bike at home with those bolt-on parts.

At the time, I had a custom motorcycle shop in Marbella in Spain. I was new to the business, ambitious and saw an opportunity with the Yard Built project – I wanted to build a bike to put the shop on the map. It was a great platform to really show the world what we were capable of.

I went to an event in Biarritz called Wheel&Waves – my staff and business partner at the shop thought I was just going to have a jolly as they didn’t understand the way this industry worked and let’s just say they weren’t to happy about it – but whilst I was there a friend introduced me to the founder of the Yamaha Yard Built program, Shun Miyazawa.

We had a laugh, we had a beer and a chat, we exchanged business cards, and two weeks later I got an email from Yamaha saying, ‘We want you to do this build, we’re going to send you a bike and we’re going to give some cash toward the build.’ I forwarded that email to everybody in the shop who were all still annoyed that I’d gone and all of a sudden, the mood changed, they thought, what a great idea it was to go to that show.

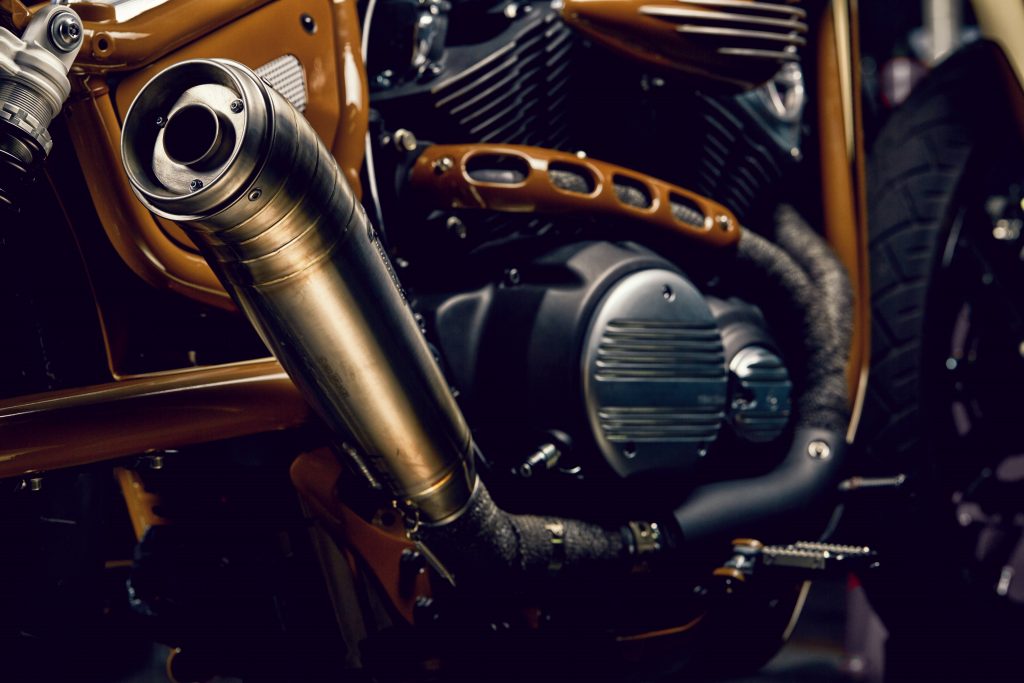

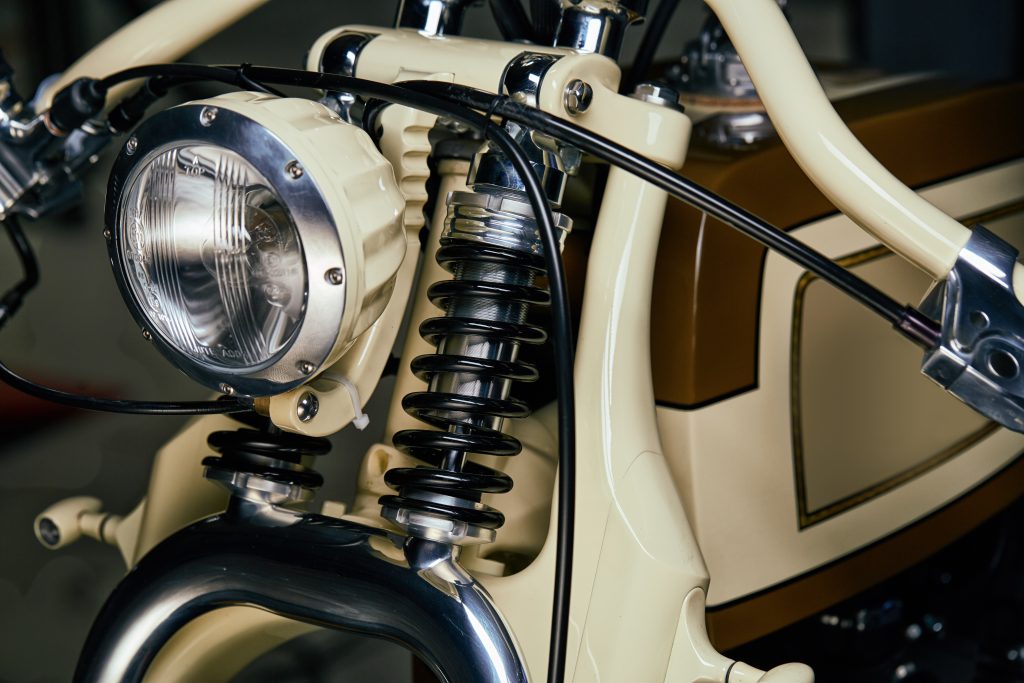

We built the bike and in the end spent about thirty grand – most people or shops spend five to ten. I custom built all the metalwork; the fuel tank, the fenders, the exhaust pipe, literally all the sheet metal we could. We also designed and had machined a tonne of billet parts, from our own 21inch wheels with matching brake discs and drive pulley to cam gear covers with plexiglass windows so you could see the cam gears in the engine running. We also did a right-side crankcase cover and left side front drive sprocket guard all manufactured in Italy by my friends at Rebuffini Cycles to the highest possible quality. It was a very cool bike.

We called it ‘Playa del Rey’ after the place in California where they built the very first oval banked board track motordrome, and was also painted by a guy, also called Ray, but spelt differently. I had not met anyone as good as Ray (Hill), who was living in Sweden at the time. I was so impressed I literally gave my house to Ray and his wife to get them to stay in Marbella until they found their own place. I then converted my office into a paint booth to give him a space to paint our bikes, hence the killer paint work on the Playa del Rey. Usually, a painter will be fantastic at something specific, such as pinstriping, airbrushing, panel work… but Ray is great at all of it and his finish is fantastic.

One of my heroes, Shinya Kimura, did a Yard Built at the same time and Yamaha wanted to launch both bikes at Wheels&Waves in Biarritz in 2015. Together, with about 25 members of the press, we rode for three days from Barcelona to the show. They filmed and photographed us riding these great roads, unfortunately we only had a day of sunshine and then 2 days of horrendous thunder and lightning storm. It was madness.

My bike was pristine, like a show bike that you’d look at and go “no one rides that thing,” but I rode it hard. The journalists were on XJR1300s and trying to catch up. I’m there in the wet, nearly with my knee down going round corners having an absolute blast. By this point most of the journos thought I was a madman!

I could hardly stand up by the time we arrived. I’d done about 1600 miles on this more or less rigid motorcycle. It had suspension, but the rear was set up rock hard to avoid contact between the frame and the rear fender as this was the first official ride on the bike. The front used a billet aluminium springer fork, hence why my back was so sore.

I thought, ‘I’ll go to the hotel, have a bath and chill for an hour’ but I had to get the bike cleaned and do a bunch of press interviews in 30 mins. It was chaotic.

Afterwards, Yamaha took the bike on tour for a year around the world. So many good things were happening, everything was moving around me, and the phone didn’t stop ringing. People wanted to chat with me about the bike, it was a big deal for the shop and it was a big deal for me at the time.

Unfortunately, it was like rising to success but crashing and burning at the same time because in the end I had to walk away from the business. My business partner and I had irreconcilable creative differences after this build and I decided to leave my business, and the bike, behind. Sadly, I think it’s still just sat in the corner of my old shop, collecting dust.

I was upset at the time, but in Spain there’s a saying – major solo que mal acompanado – it’s like you’re better off alone than in bad company and so yeah, it cost me what it cost me, but I’ve always said the best revenge is success. I had to leave to be happy, and in hindsight it was a great life lesson. I believe that everything happens for a reason.

If I could get that bike back, I’d definitely keep it, and I’d ride the sh*t out of it. There are a few little bits I’d change to make it the exact vision that I had in my head when we started the build – I had some external creative input from my staff that I wasn’t keen on that ended up on the final bike.

I’d get rid of the speedometer that sits on top of the handle bars. To me it’s out of place right on top and ruins the clean lines of the bike. I’d also change the handlebars. The design was a homage to a board track racer and I wanted to make a different set of handlebars for it, but I screwed the first set up and ran out of time before the unveiling. Instead, I used an old set of modified Harley bars and flipped them upside down and ran them backwards on the bike – it worked, but it wasn’t quite exactly how I wanted it. Other than that the bike is absolutely bang on. If only we could be reunited.”

Read more

Trailblazers: Seven collectible motorcycles to watch

Read all about it: The rise of the £450 bike brochure collectors are going wild for

Like grandfather, like father, like son: the third-generation exhaust fabricator saving Britain’s classic motorcycles