“I was burning along through the Free State and there, under a tree, was a police car, but no sooner had I seen it than I had rocketed past it; the chap snoozing away inside must have woken up with one hell of a start. The GTO had two outside exhaust systems that produced the most impressive sound you can imagine. About 30 miles down the road, there was a town called Harrismith into which I was going to have to pass and as I approached the bridge I was required to cross in order to do so, I saw it was blocked by a whole crowd of people and cars and thought damn, the policeman has radioed ahead and trouble is waiting for me, but I drove straight through. I don’t know what on earth they were looking for but, there it was, a bit of luck!

I had such fun with my Ferrari 250 GTO in South Africa during the late sixties, it was such a wonderful machine and in those days the roads were well made and almost completely deserted. You might visualise the vistas as tundra, but it’s much more lively than that; imagine driving towards a wide open horizon through low bush and brushland on a long, straight road with the occasional curve to catch you out. Wonderful!

I set two or three quite impressive records burning between Johannesburg and Durban, often making the 500 kilometre trip there for lunch. I always had a passenger but it was unnecessary to shoot a line [and big-up the car] because the 250 was brilliant and cruised comfortably at 140mph. With a five-speed gearbox, it was an easy car to drive well and exciting to drive on its limit, but such was its handling you always knew where that limit was, it was just a question of establishing where your limit was, something which fortunately I had a certain facility for.

It’s almost an indefinable thing, some people feel it more than others and some probably never feel it at all, but the sense of knowing that you’re getting close to the wind in a car is a sense, and when I got into the GTO to test my mettle, that feeling sort of transmitted through my bum. The three litre engine produced around 250bhp and was unburstable. If I ever regretted selling a car, this is the one, but the money it released enabled me to buy an Alvis, with which I was able to court my future wife Liza, with whom I went on to have two wonderful children.

My first car was a second hand MG TD that my parents kindly laid on when I was 18 and off to university in Leeds. We lived in Huddersfield so I needed transport but they were completely against my doing anything competitive with it. I joined the university car club, the Yorkshire Sports Car Club and the British Automobile Racing Club and thought I was the coolest thing in town, as every young chap does with a little red sports car and some pocket money to spend. I was always going somewhere, or escaping from something, I don’t think its engine was ever completely cold, and I turned it into quite a hot little car to get it ready for the local hill climbs, sprints and driving tests. That car launched me into the motorsport world.

In 1957, I got a Le Mans Replica Frazer-Nash that was part 21st birthday present and part exchanged for the TD. It was an absolutely brilliant car, but girlfriends got frozen in it. The army caught up with me in 1959, and after doing my national service, which I enjoyed very much, I came home from Germany, got a job in the textile industry, fell out of love with that and decided I wanted to increase the rather small impression I’d made on the motoring scene by dedicating my time to racing – which gave my parents a real fright.

Financed by a small bequest from a granny, I plumped for an ex-works D-Type that belonged to Mike Salmon and having been an ex-Ecurie Ecosse car, it was dark blue, but I immediately resprayed it British racing green. I had some great battles in it with Jimmy Clark, but at my first big meeting of the 1963 season I smashed it in a big way at Snetterton. There were two well known chaps in front of me, Graham Hill and Jimmy Clark, and although the D was brilliant in the wet, on this occasion it aquaplaned in a stream of muddy water that was running across the track exactly where I had to put the brakes on to make the hairpin at the end of a long straight. It spun towards a marshal’s post, hit it and rolled. It all happened quite quickly but I experienced it in slow motion, which some people do when faced with something like that, so I could see exactly what was happening.

I’ve been saved by being thrown out of a car, and I’ve been saved by being strapped into a car, but I would probably have been crunched up quite badly if I hadn’t been chucked on to the track that day; I’ve still got the cracked helmet I was wearing.

We all took our racing seriously because racing was dangerous back then and that was what I liked about it. You hit trees, fell over embankments and stood a very good chance of not going home at night. Retaining an awareness of the potential for disaster was part of the excitement; knowing that if it goes wrong, you’re toast. Nowadays I find it’s too sanitised for me, but I’m pleased people aren’t being killed the way they were.

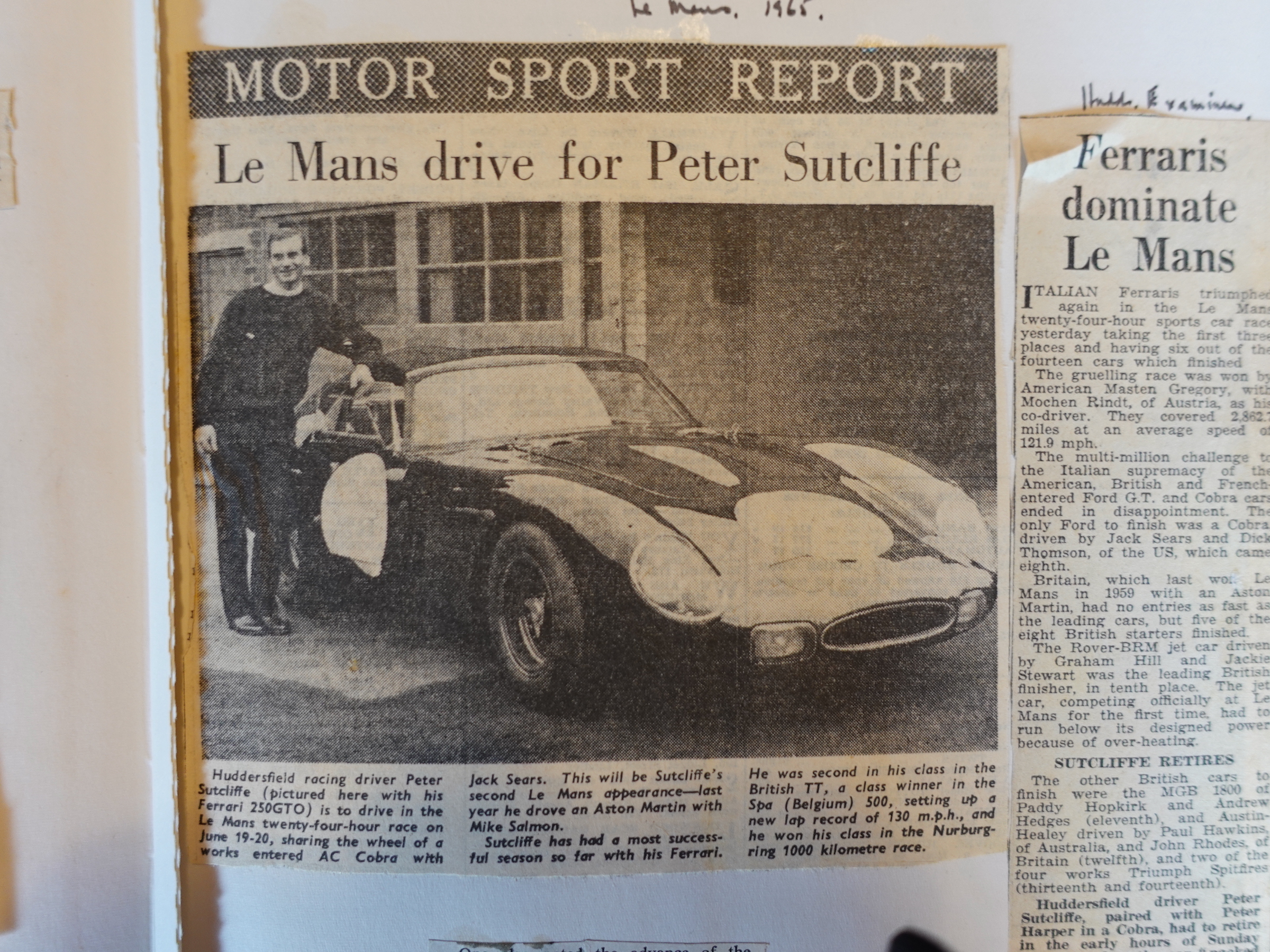

I’d been chasing GTO Ferraris and was fed up with looking at the back of them; the only solution was to buy one. David Piper, a friend of mine, wanted £4000 for his bright BP green one. He wasn’t very negotiable, but it was amazingly fast and it was one of the ones I’d been following so I finished up with it at the end of 1964 and set off across the continent racing European circuits.

I had it repainted in dark green metallic, which was my racing colour, and went on to win a lot of points for Ferrari. I made the huge mistake of racing it with red wheels, just the once, before changing them to silver, but somebody decided to create a limited edition model of it in that exact configuration. I have one of the eighteen.

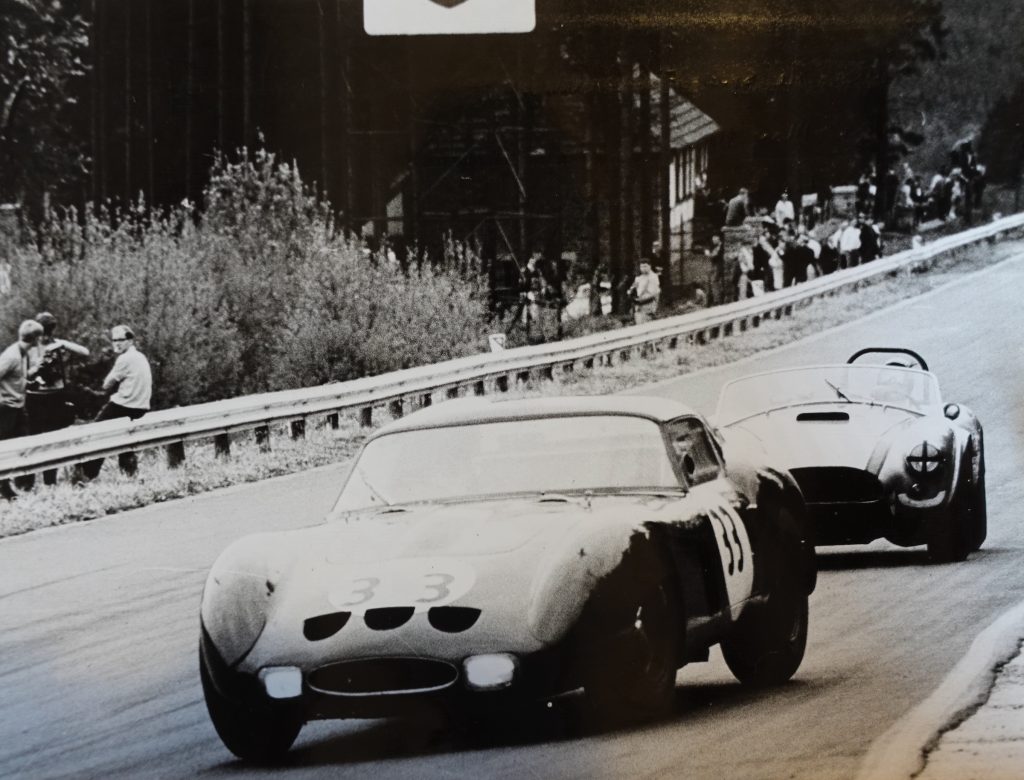

Grand Prix drivers were also involved in sports car racing and grand touring back then, which meant I would be chasing, or being chased by the likes of Jackie Stewart – the competition was great. Roy Salvadori and I had a lot of good tussles, but I was a privateer so I could never thrash my cars because that was when the bills would start to come in.

Paddock life was more relaxed than one would find nowadays, there were lots of celebrations and commiserations depending on how things had gone, and we would help each other with parts if anyone was stuck. It was such a wonderful atmosphere, and that sense of duty and good behaviour extended to the track; you could trust people to do the right thing within their capability, people who weren’t as fast would get out of the way.

The thing about the GTO was that it would do everything that I wanted it to do, so I knew it was never going to get me into trouble. I, on the other hand, might get it into trouble. It was my friend, but when the Ford GT40 came along it was no longer required. I advertised it for £3000, but the phone never rang and no letters came. Nobody was the least bit interested in it, and my parents were fed up with my accumulation of cars, so I was in a bit of a quandary.

I’d met some nice chaps racing in South Africa and they said if I sent it over they were sure they’d buy it, so I shoved it in a container as quickly as I could and off it went to what I hoped was going to be its new owners – but that wasn’t to be. I followed it out there in the winter of ’65 to race in the Springbok Series with my GT40 to discover they didn’t want my GTO.

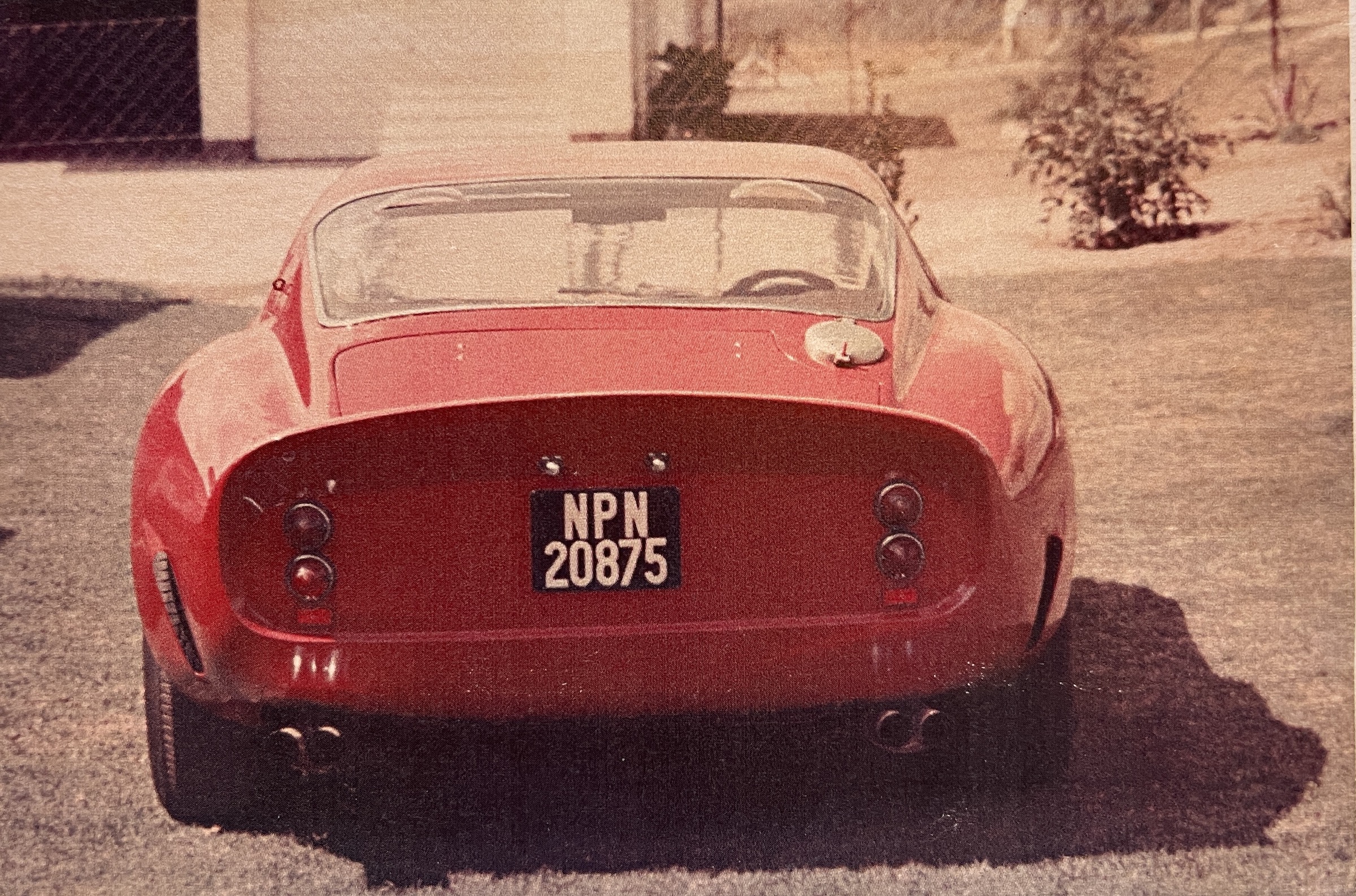

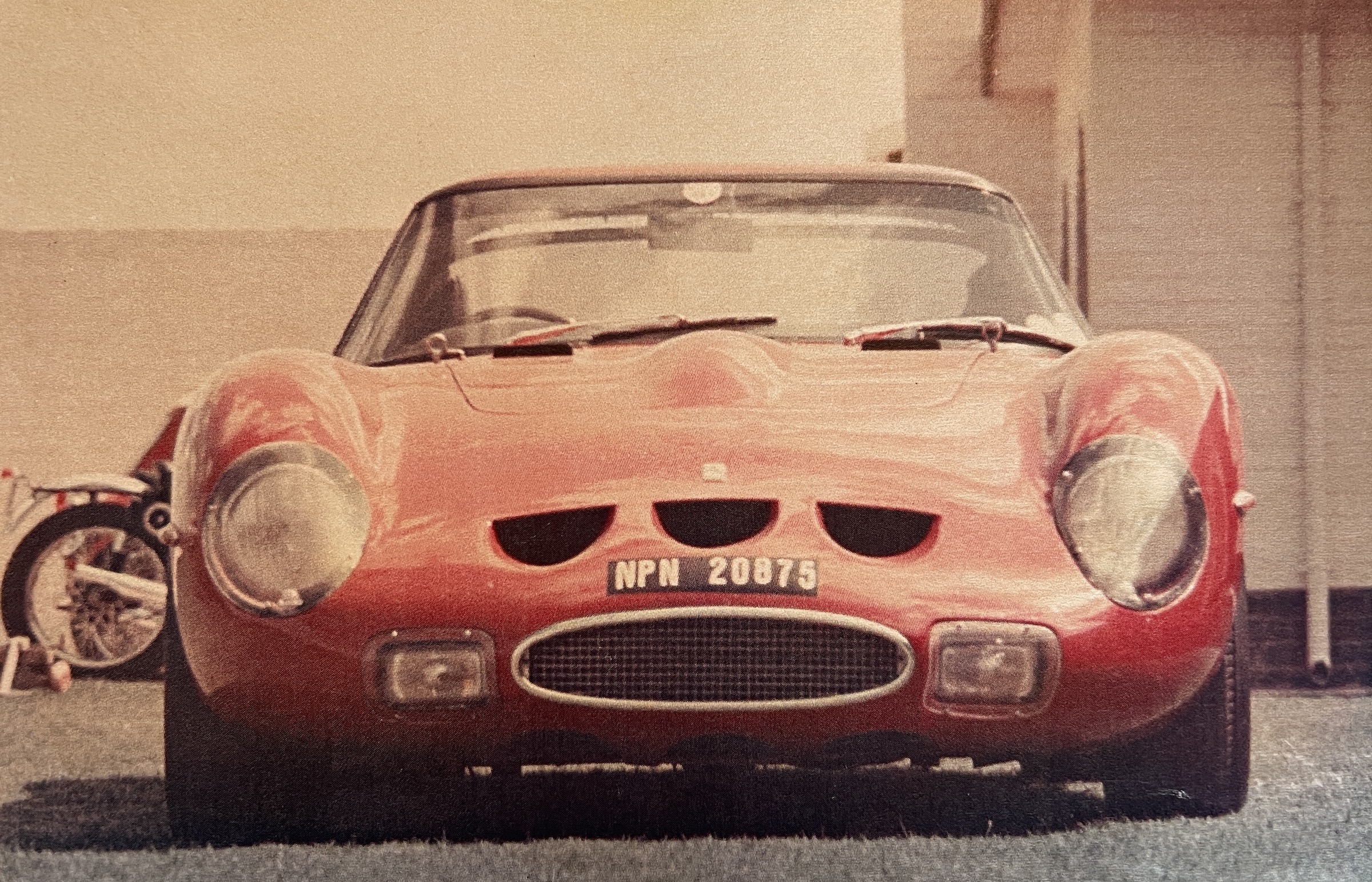

I then emigrated to South Africa to take up a position with an engineering company and the GTO was sitting there covered in dust. My friend, Bruce Johnstone, a South African racing driver, bought a share in it and we had it rebuilt to its conventional road car configuration. I had an original Scaglietti windscreen sent out to raise its profile, to civilise it we trimmed the interiors, and because it was no longer a racing car we resprayed it good old ordinary Ferrari red.

In 1969, quite out of the blue, David Piper phoned me up from Italy and said ‘do you still have that old GTO because I want to buy it from you’. Once again, I couldn’t get it into a container quickly enough and to ensure safe passage I insisted on it being stowed under deck so there was no likelihood of it being washed off if it had a rough trip.

David paid around £20,000, which was a very good price at that time, and I thought wow, bonanza, bonanza, I’m rich! But of course, over the years they have gone up quite nicely in value. My father, the director of a building society, took payment for the GTO on my behalf at a filling station on the M1. He was very straight down the line and with £20,000 in cash he must have been terrified that someone might run into the back of his two-litre Rover on the way home.

The GTO is the car I wished I had kept but of course that regret is to be offset with what happened next. I came over to England to do the FIVA International Rally, which was taking place in Harrogate that year, and using some of the money from the sale of the GTO I bought an Alvis to do it in. I had just met Liza and cheekily phoned her up to ask if she’d like to come. Being a free spirit, she said ‘sure’, and despite having no experience in rallying, she had a wonderful attitude and we did very well. I think we were the only couple on this rally of 300 cars that weren’t married but that wouldn’t be for long.

I know exactly where the GTO is today, it was bought for around 48 million dollars [We haven’t been able to confirm that sum. Ed] a few years ago [in 2013] by Johann Rupert, one of South Africa’s richest men, and entirely rebuilt. I believe it’s entombed in England somewhere and is part of a huge collection of cars that will probably never turn a wheel again which is tragic. All cars are meant to be used, abused and enjoyed. They’re living things if you give them a chance and the GTO was very much a living car. Time passes, things come and go, and nobody is ever going to have the fun in the GTO that I had. I shall probably never see it again, but if somebody offered me a drive in a GTO, I’d say yes please.

Read more

Monterey 2022’s highest sale is this £18.7m Ferrari 410

The One That Got Away: Why Derek Bell let go of the Ferrari of his dreams

Hands off at 250 mph – the life of a Bugatti test driver

Slight correction – not $48m, but 25% of that – 12 years ago….

and not “entombed” either – it is driven……

The rally in Harrogate was not “Fever” but F. I. V. A.

It raced and hit the Croft chicane damaging a RED front wheel….

Car was prepared by Crostune in Barnsley…the damaged wheel is hung in the man cave …

If you’re in touch with Peter Sutcliffe, Please ask him to email or call me.

derek797@hotmail.com Tel +01 (425) 466 4375

GSB, Cape Town friends, Bellevue near Seattle, WA USA and Linda says “Hello”