Citroën first presented the 2CV at the 1948 Paris motor show, to a chorus of flashbulbs popping as the presence of Vincent Auriol, president of the Republic of France, added to the crowds at the Grand Palais on the Champs-Élysées. In reality, it was the product of a laborious, 12-year development process that involved fireflies, a war, and the Volkswagen Beetle. Had the Nazi army stayed out of Poland, the Citroen 2CV would have arrived in 1939 as a completely different car.

Michelin began studying ways to motorise the masses in the early 1920s, presumably as a way to sell more tyres. Its executives lamented that cars were 15 times less common in France than in America, where even farmers could afford something rudimentary like a Ford Model T. Cars were a common sight in the posh parts of cities such as Paris, but the French countryside still looked like the Middle Ages with the exception of a few motorcycles and bicycles. Michelin asked the dealerships it worked with to survey their customers about their transport needs. It asked the amount of money they were able to spend on buying a new car, the number of seats they needed, what they planned to do with it, and the maximum speed they hoped to reach. The survey’s results underlined the need for a cheap, basic form of transportation. Of course, Michelin manufactured tyres, not cars, so it couldn’t alone fill this gap in the market.

When Citroën filed for bankruptcy in 1934, the situation changed. Michelin already owned a big stake in the French car company, so it bought the rest of it and launched a far-reaching restructuring campaign to cut costs. One of its first moves was canceling the V8-powered 22CV that Citroën spent years developing as its flagship model. Michelin’s influence helped convince Citroën to begin looking at market trends and customer demands, and it realised that 90 per cent of first-time car buyers chose a used model to save money. Clearly, the market still lacked a basic, affordable, and reliable car designed for those upgrading from a humble moped.

Armed with over a decade of market research and a team made up of its most intelligent engineers, Citroën began developing an entry-level model in 1936. It was referred to as the Toute Petite Voiture (TPV), a term which means “very small car” in French, and it was envisioned as the prescribed treatment for the problem of rural transportation. Pierre-Jules Boulanger, a Michelin executive who became Citroën’s president in 1938, played a paramount role in moving the project forward. He spent his days in the research and development department, not behind a desk, even testing every prototype built.

The brief for the Citroën TVP

On paper, the project’s guidelines were simple. The TPV had to carry four adults and up to 50kg of cargo, use front-wheel drive, and weigh no more than 350kg. Boulanger also formally requested three forward gears and hydraulic brakes all around. Above all, he insisted the car needed to be extremely cheap, so any semblance of luxury was ruled out from the start of the project.

“[It needs to be] a bicycle with four seats, with a cabin that keeps rain and dust out. It has to be capable of cruising at 37-40 mph in a straight line on a flat road, and it must be affordable enough for a blue-collar worker to buy and use daily. I want owners to drive 30,000 miles without having to change a part,” explained Boulanger. “It replaces the bicycle, the motorcycle, and the horse-drawn carriage.”

One of the most important points on the design brief was that the TPV needed to be easy to repair by someone who knew absolutely nothing about cars. Achieving this required reducing the number of moving parts to the bare minimum and ensuring everything was easily accessible.

While the TPV was astonishingly simple, it became the most complicated project Citroën had ever launched. Working under the guidance of André Lefebvre, a former aircraft designer who joined Citroën in 1933, engineers tested a motley selection of ideas that ranged from practicable to absurdly far-fetched.

Some of the brave but ultimately senseless solutions included replacing most of the body panels with pieces of oilcloth draped over a metal frame, and, later, fitting a pivoting hemisphere-shaped panel on each side instead of two conventional doors. Citroën also considered using wood in the TPV’s construction, which wasn’t unusual in the 1930s (even DKW still made wood-bodied cars), and some wanted to give the car unibody construction like the Traction Avant released in 1934.

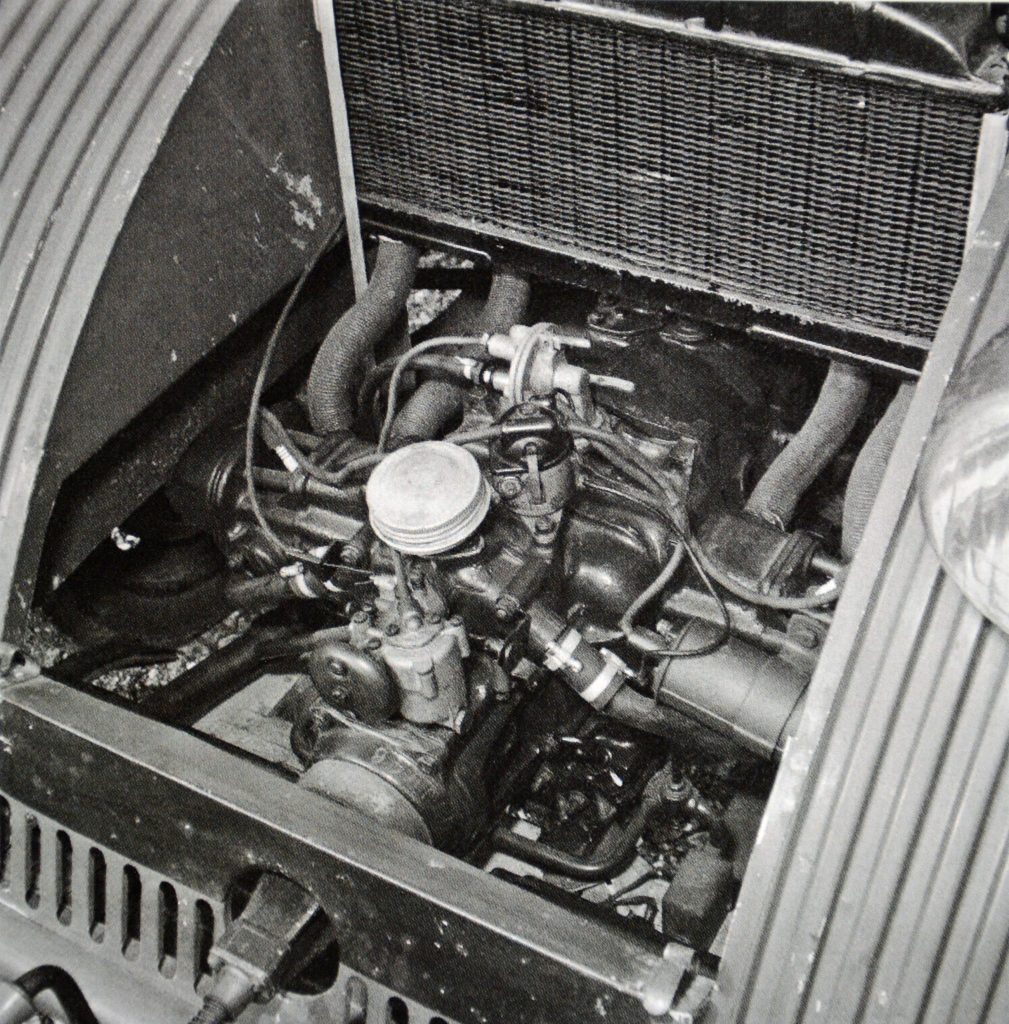

Prototypes received a dizzying selection of engines ranging from one to four cylinders (including two-strokes), plus manual and automatic transmissions. What nearly everyone agreed on was that the TPV didn’t need a battery in its electrical system. Installing one would fly in the face of all wisdom by making the car heavier, costlier, and more complicated. It would use a magneto, like a moped, and either a hand crank, a kick starter, or a lawn mower-like pull cord to start the engine. And, because it had no battery, Citroën even assessed the pros and cons of using fireflies kept in a body-mounted jar as parking lights.

Citroën gradually weeded out the ideas deemed too technically unmoored (including, say, breeding fireflies) and retained those it believed it could realistically bring to production. Executives planned to introduce the car at the 1939 Paris auto show, so the project was fast-tracked.

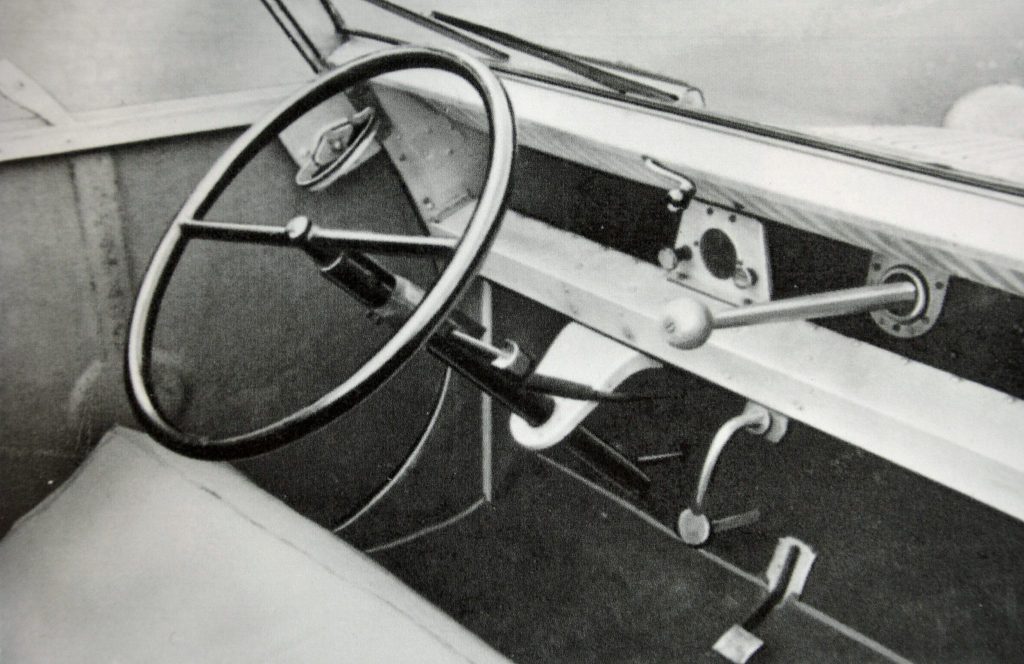

Engineers chose an eight-horsepower, 375-cc water-cooled flat-twin engine and a three-speed manual transmission, which was operated through a horizontal lever that stuck out from the dashboard. And, after much deliberation, the pull-type and kick starters were abandoned in favour of a crank.

Styling was considered a necessary encumbrance, so the TPV was an exercise in function-over-form design. It wore a single headlight, its body was made with Duralumin alloy, and it wasn’t equipped with exterior door handles. Early prototypes had windows that pivoted down, but the glass was redesigned to pivot up because French law dictated drivers needed to be able to put their arm out to signal. It was cheaper than installing semaphores or indicators.

The TPV was just as rudimentary inside, where the only gauge on the dashboard was a voltmeter. Hammock-like seats hung from roof pillar-mounted ropes, and Boulanger commented users “could make their own pillow” if they wanted to sit on something softer. The lone windshield wiper was manually operated.

With the basic design agreed upon, Citroën turned its attention to marketing the TPV. It defied accepted notions of a car, so sales personnel needed to learn how to sell it, and motorists needed to learn how to drive it. To keep costs in check, dealers were asked to slash their profit margin from 18 percent to 10 percent. Documents sent to Citroën stores across France made no attempt to sugarcoat the TPV’s performance.

“The fact that the TPV is not fast makes taking a certain number of precautions very important,” explained Boulanger in a letter written in April 1939. He recommended staying as close to the right side of the road as possible (many country roads weren’t, and still aren’t, marked), and looking twice before crossing an intersection. He also stressed the TPV shouldn’t be let loose in mountainous regions. “Do not drive up a road steeper than 12 per cent. Take a detour instead. On more gentle hills, put the transmission in second or first gear and wait calmly until you reach the top. Do not drive down a hill that’s 12 percent or steeper with a full load of passengers, or down a 7 percent hill that’s about three kilometres long.”

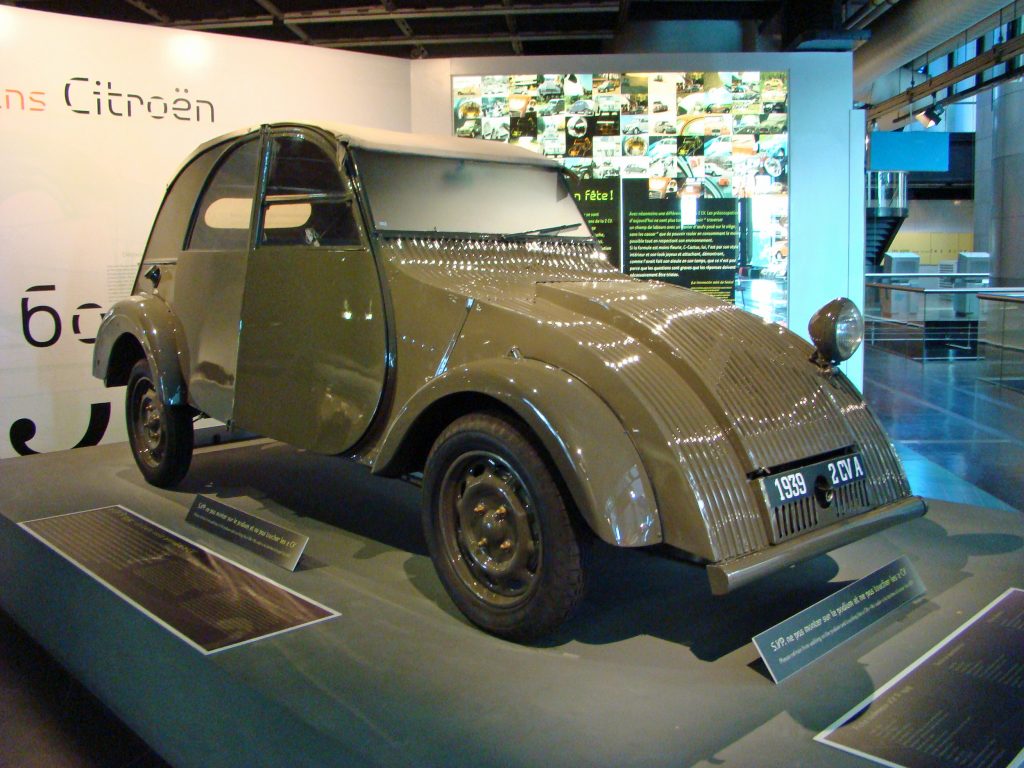

Everything went according to plan, so Citroën had one last major hurdle to clear before introducing the TPV at the 1939 Paris show: obtaining certification for sale. French authorities homologated the car as the 2CV A on August 28, 1939. Citroën’s Levallois factory began building 250 pre-series cars that were to be sold to Michelin employees the following day, but production abruptly stopped when France joined the United Kingdom in declaring war on Germany on September 3, 1939. Citroën’s focus shifted from putting farmers on wheels to supporting the war effort, and the 1939 Paris motor show was canceled.

War stops Citroën TVP development

One extremely important and often overlooked detail is that the 2CVs built by Citroën in 1939 were not prototypes or test mules; they were road-legal production cars with serial numbers. The number of cars manufactured before France entered World War II remains a matter of debate among historians, and Citroën has never been able to shed light on the matter. The only clue we have is a transcript of an executive meeting held in September 1940, three months after the Levallois factory was bombed, which notes approximately 100 cars were put in customer hands before production stopped.

Citroën never abandoned its plans to put France’s most rural residents on wheels, and launching the 2CV arguably became even more important after World War II than before. It secretly resumed the car’s development in 1941 and made numerous changes in the subsequent years; the design evolved, the body was made with thin steel, the flat-twin engine became air-cooled, and the suspension was fully redesigned. Citroën finally introduced the 2CV at the 1948 Paris motor show, loading it through a window to keep its final design under wraps until the opening day.

Rarely had a new model inspired so much dislike from the general public. Most visitors found it blisteringly awful, but the wind quickly turned in its favour. Approximately five million examples of the Citroen 2CV were built until production ended on July 27, 1990.

Citroën explained that part of the reason why the car changed so much during the 1940s was to ensure the Germans didn’t copy it. In July 1940, a team of engineers sent by the German government arrived at Citroën’s headquarters and asked to see the 2CV. After closely examining unfinished examples lingering on a battered assembly line, they declared their intention to haul three cars back to Germany, where they would be personally scrutinised by Adolf Hitler. Some members of his staff would be shown the car, too, but the German engineers pledged to keep it away from anyone involved with the nation’s automotive industry. In exchange for this unpalatable favour, Citroën would receive what a 1944 letter simply describes as “a people’s car” to build and sell in France. Ferdinand Porsche, the man who designed the first Volkswagen, would be available to answer any and all questions Citroën had about the model.

This anonymous letter in Citroën’s archives department is not signed, so we don’t know who wrote it or who it was addressed to. Citroën remembers it turned down Germany’s offer six times, so the government took a different approach. It shipped a people’s car to Paris and hoped the company would change its mind after seeing it. Someone from Citroën stepped outside, ordered workers to put a tarp over the car, and asked everyone present to ignore it. German officials took the vehicle back and never returned, according to the same letter.

For years, all that remained of the original 2CV/TPVs were a handful of images covertly taken during testing. One early unit that had been chopped up into a pickup enigmatically ended its days at a Michelin test track, but its front end looks nothing like the final production car’s. The pickup was bought by a collector and restored shortly before it was due to be scrapped. It’s now in a private collection located near Lyon, France.

The hunt for the missing 2CV As

In 1968, one of the cars was unexpectedly found in pieces, in a box, at Citroën’s La Ferté-Vidame proving grounds (about halfway between Paris and Le Mans). It was reassembled by the same man, chief road tester Henri Loridant, who took it apart. Citroën gave it a full restoration.

One car was better than none. In the following decades, historians investigated the occasional nod-and-wink tip claiming a pre-war 2CV was gathering dust in the back of a garage, sinking into a dense forest, or stashed at the bottom of a scrap pile in a remote part of France. None of these led to anything, and the first batch of 2CVs became another mystery shrouded in the fog of World War II. The official explanation that every single car was destroyed, either by the factory or by the German military, was accepted.

Then, in 1994, a long-time Citroën employee named Jean-Claude Lannes drove to La Ferté-Vidam to pick up some materials and heard there were some old 2CV parts left in an attic. After climbing up, Lannes found himself face to face with three pre-war 2CVs that even the company had mislaid. It was the breakthrough everyone had dreamed of. His excitement was cut short when he learned the cars needed to stay there indefinitely, because extracting the trio of cars meant removing the building’s roof, an arduous task no one wanted to fund.

Citroën later changed its mind and presented the cars in as-found condition at Rétromobile in 1998, to celebrate the 2CV’s 50th birthday. Workers cut a hole through the roof by removing the tiles and sawing off part of the wooden frame, and hoisting them to the ground. All three are still unrestored (at the time of writing), part of Citroën’s heritage collection in Paris. Who hid them, when, and why remains a mystery.

That’s where the pre-war 2CV’s story ends, at least for now. Reports of additional cars stashed in rural France emerge from time to time but all have proved to be dead-ends. And yet, there are so many cars hiding in the countryside, either in fields or in barns, that there could be other examples waiting to be discovered.

The hunt for the Toute Petite Voiture goes on…

Via Hagerty US

Read more

As ex-2CV owners, bonkers and good fun……an interesting article. Thank you.

Great article. My abiding memories are of the Rosbifs and Snails trip to Monte Carlo 13 years ago. The website is still up at http://www.rosbifsandsnails.co.uk

We raise £85k for the Thames Valley & Chiltern Air Ambulance! The little snails did well 😉