If you’re not deeply involved in the veteran vehicle scene, visiting the London to Brighton Veteran Car Run presents a unique opportunity in the motoring world: To experience cars, motorcycles, and even bicycles, that you are utterly unfamiliar with.

Poke around anything built in say, the 1960s, or even a lot of pre-war vehicles, and most of what you see should look quite familiar. But with controls like railway signal boxes and shapes that share more with horse-drawn vehicles than the road transport that followed, veteran vehicles are a whole new world of mechanical and aesthetic intrigue.

Thankfully, we still have their owners to tell us more about them. So at this year’s London to Brighton, we caught up with the owners and operators of two veteran cars, a veteran motorcycle, and a 118-year-old bicycle, to learn what makes them tick – and to see whether 2022’s foul weather had dampened their spirits…

Jonathan Procter – 1898 Panhard et Levassor

Aside from the joy and determination of the people involved, it’s the details that really make the vehicles that enter the Veteran Car Run. And everywhere you look on Jonathan Procter’s 1898 Panhard et Levassor, there is something to admire.

Take the large, central lamp in front of the exposed fins of its radiator, joined by a couple more in closer reach of the driver and passenger. Or the large, curled horn down by the driver’s side, the complex arrangement of controls just in front, or perhaps the shapely wicker luggage basket behind the seats.

What you cannot immediately make out is the engine. “It’s a twin-cylinder” says Procter, “and it cruises at about 40 miles per hour, actually – which is quite impressive for a car of this age.”

The bodywork above it is interesting too, aside from the details apparent from a quick poke around. “The rear of the body actually detaches. So it’s got another two seats which go on the back – normally I run it with four seats, and bring my children along. But this year I’ve made it a bit more racy!”

Other than a detached battery lead along the route “which stopped it dead – that was a bit of a worry for a few seconds…” the car made it to Brighton with little trouble, Procter being among the first to arrive, shortly after 10am. But it’s far from his, or the car’s first rodeo.

“I’ve done the London to Brighton a few times. And once on one of those tricycles…” he gestures to a quirky-looking machine parked nearby “I rode from John O’Groats to Land’s End, in my twenties…”

In a car all about details, one item in particular catches my eye – a long pole that drops down from the side of the car towards the ground.

“If you’re going up a hill,” explains Procter, “the brakes don’t work very well if you start to roll backwards. So the pole sort of drops down and drags along the ground, and digs in like an anchor.”

I could spend all day walking around the Panhard et Levassor, frankly, but perhaps the only thing better than doing that would be learning what everything does and experiencing it all in action.

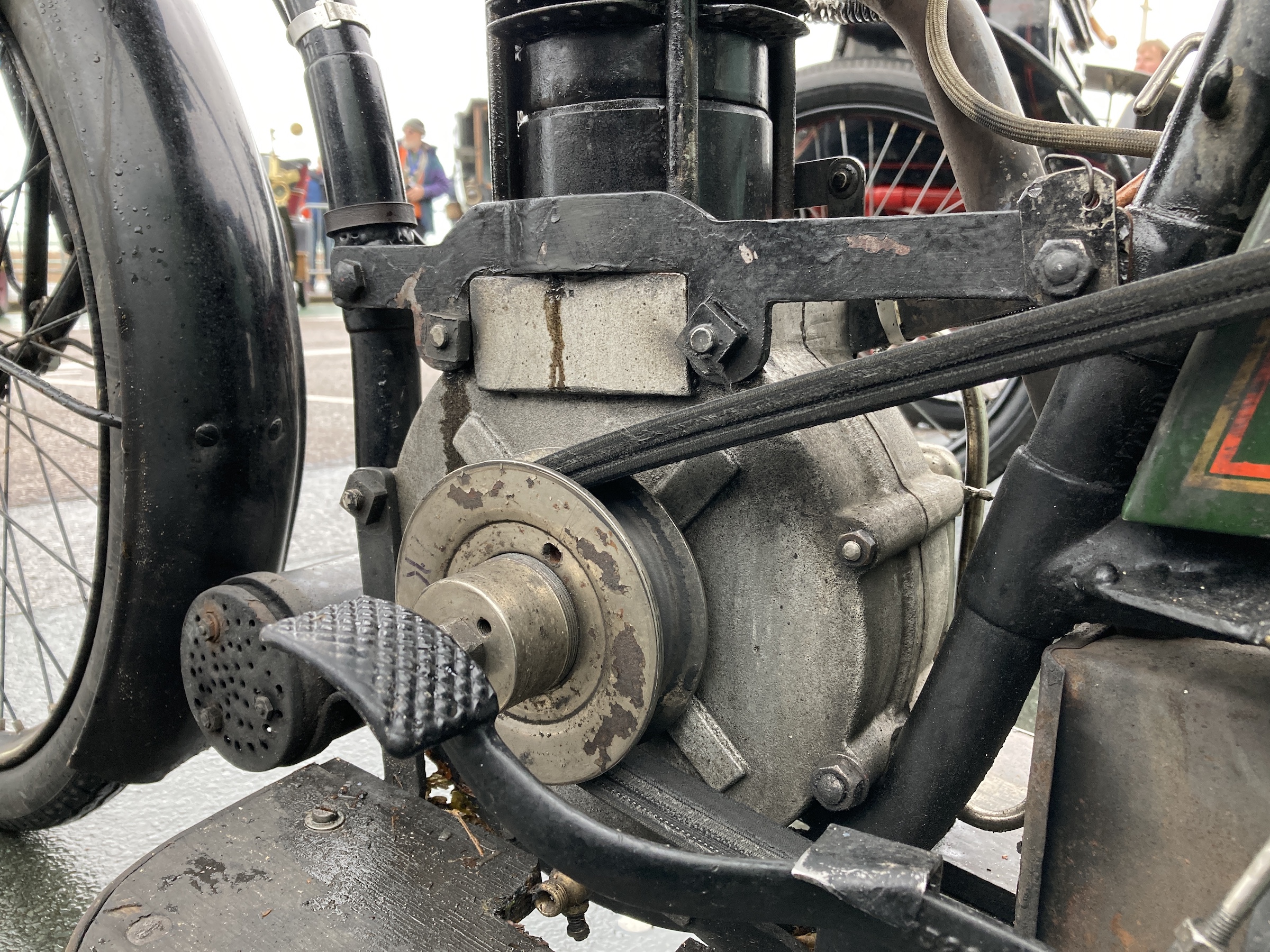

Mike Wild – 1904 Dreadnought motorcycle

If some of the cars in the London to Brighton look somewhat precarious, Mike Wild rides across the finish line with surprising ease and a kind of runaway haste on Dreadnought – a 1904 special powered by a De Dion Bouton single-cylinder car engine.

“It’s one of a kind,” Wild explains as he removes his Union Jack-painted pudding-bowl and shakes off his sodden leathers. “Built in 1904 by a gentleman called Oily Carslake”. A brilliant name seems to be de rigeur for the period, doesn’t it?

“He decided he wanted to have a unique motorcycle, and it’s powered by an 1899 De Dion Bouton engine – and he paid, I think, £2.50 for it. Anyway, it was in quite a state, so he put the engine into a different frame, and rode it in many events.”

Given the somewhat brisk way that Wild rode into the paddock, it’s clearly far from conventional – and Wild pre-empts my next question. “If you look here, it’s a single-speed, with a belt drive, and no clutch. The engine has to be capable of going down to walking speed, and accelerating away.

“The engine has a cam on the exhaust, but it’s an atmospheric inlet – so when the piston descends, that draws in the air and fuel. And if it doesn’t do that quick enough, you stop! It’s not been right for a while, it used to be all or nothing, but I’ve brought back that low-speed characteristic.”

The weather didn’t make things easy on the way down, Wild describing conditions as “absolutely dreadful”. The bike became waterlogged twice, so there were a couple of stops to dry it out before Brighton. But it’s amazing it made it at all – and comes with an important job to do.

“It’s owned by the Vintage Motor Cycle Club, and they want to see the bikes being used. And what I really want to do is encourage someone younger to say, ‘next year, I’m gonna ride it’ on this event. For Wild, it was his first – ticking off a bucket-list item – but perhaps next year, that honour will fall to someone else.

Ben Coles – 1900 De Dion Bouton Motorette

It takes me a minute to figure out who is driving car 29 in the Veteran Car Run. There are four people aboard, and the front pair are facing backwards. This is what’s known as a vis-à-vis, an arrangement that will no doubt come back into fashion when cars drive themselves someday.

But after a little investigation, it’s a man named Ben Coles who steps forward as the driver, having worked the tiller all the way down from London – a control method that also makes a driver hard to spot when it’s in amongst a forest of legs.

“It’s an 1899 De Dion Motorette” explains Coles, “built in 1900, and the oldest one in America – it’s an American-spec car. It’s the third London to Brighton for the car, and its third finish. We were determined to get here for 12 o’clock, so we’ve gone hell-for-leather to get here before twelve!”

Despite the weather – and the Motorette’s lack of a roof to keep it out – there were no problems en route though. “It’s been reliable, just fantastic. We lost a headlight. And the other one smokes a bit, but we’re not bothered about that…”

A cruising speed of 12-15mph turned out to be more than sufficient to make Brighton before noon with the 7am takeoff – and that vis-à-vis layout no doubt made it a sociable drive too. “Occasionally you have to sort of lean to the left or right to see around them!”

Coles has owned the car for five years – buying it after it failed to sell in a Bonhams auction, perhaps on account of its condition at the time – and has needed to build a lot of parts from scratch to bring it up to its current standard. “I rebuilt it when I bought it, and I’ve done every ‘Brighton since.

“Mechanically these cars are often quite worn-out when you get them, so you have to go through them until they’re reliable. It took maybe 12 months to get it reliable.”

And under five hours to get to Brighton before midday – all while facing your passengers in the most sociable driving arrangement yet devised.

Matthew Myerscough – 1904 Swift bicycle

As we follow the route of the London to Brighton Veteran Car Run, just before we reach Staplefield village we spy a bright-orange, Gore-Tex-clad cyclist on a distinctly spartan-looking bicycle. He puts on a smile and gives a thumbs-up for photographer Charlie Magee, before reverting his focus to the drenched road surface as he free-wheels down a hill.

At the finish on Brighton’s Madeira Drive, we find out the identity of this brave soul. Matthew Myerscough lives in Cardiff but grew up in Lancashire, and completed the 60-odd mile journey riding a 1904 single-speed Swift with a freewheel and a non-original but well-aged Brooks P17 saddle, which perfectly complements the patina of the bike.

The obvious question is, why? “It’s just a bit different, isn’t it? It’s probably a bit mad but I enjoy cycling and enjoy a bit of a challenge – something a bit different – and my Dad said, ‘You know what, I’ve got this bike, do you fancy it?’ and after a couple of beers that was it. My father’s been fettling it and fixing it up.”

For the event, however, it was Matthew who chose to ride, while Myerscough Senior took to a Crestmobile – also dating to 1904. Matthew proudly boasts of how he “beat him to the halfway at Crawley” before adding, “then I set off before him and he passed me on the hill.”

Like many others that take part in the Veteran Car Run, Matthew is technically minded. His day job is as a civil engineer, specialising in bridges. “I guess the event appeals to people with that kind of [technical] mindset,” says Matthew.

“It’s been a great day but it’s bloody hard work! I was up at four this morning to get to the start.” Riding his Swift is, as you can imagine, a challenge. “The unknowns and uncertainties of the hills was a concern. The gearing, or lack of, means it really doesn’t go up hills. But I think I was getting about 10 or 12 miles an hour on the flat, which I’m pretty happy with.”

There were challenges beyond the hills. The front brake seized on, “which was a bit of an issue” says Matthew in the sort of understated manner we’ve come to expect from participants at this stiff-upper-lip event.

Brake issue aside, he’s chuffed that he’s not had to make any running repairs to the Swift. “It’s an amazing machine. I’m over the moon with how it’s handled and performed.”

Drenched through, he still has to travel back to Cardiff the same day before he can enjoy a well-earned hot bath. Will he be back? “Absolutely. But with better weather, hopefully!”

Read more

British grit and oil lamps on the London to Brighton Veteran Car Run

Why the world’s oldest motoring event matters more than ever

Veteran Car Run competitor is keeping it in the family