It might look like a humble family car but don’t be fooled, because the Citroën Xantia Activa is the supercar you’ve never heard of.

Implausible? Perhaps, but the fact is the 1995 Activa was quite unlike anything else drivers could get their hands on at the time. It was the last Citroën to truly experiment with technology, a leftfield take on the performance car, and boy did it confound the critics.

Beneath its innocent looking exterior was suspension technology not unlike that which had only recently been banned from Formula One.

The French engineers had devised a way to actively prevent roll and pitch in corners without impacting on ride comfort, and in the process they created a family car that could pull more lateral G in a corner than sports cars including the Ferrari 512TR and Honda NSX. French magazine L’Automobile reportedly proved the point, testing a Xantia Activa on a skidpad and recording 0.94 g lateral acceleration. The 512TR managed 0.92g, the NSX managed 0.93 g, while a Toyota Supra recorded 0.95g and Ferrari’s F40 hit 1.01g. It’s all the more impressive when you consider the Activa’s higher centre of gravity and relatively skinny (205/55R15) tyres.

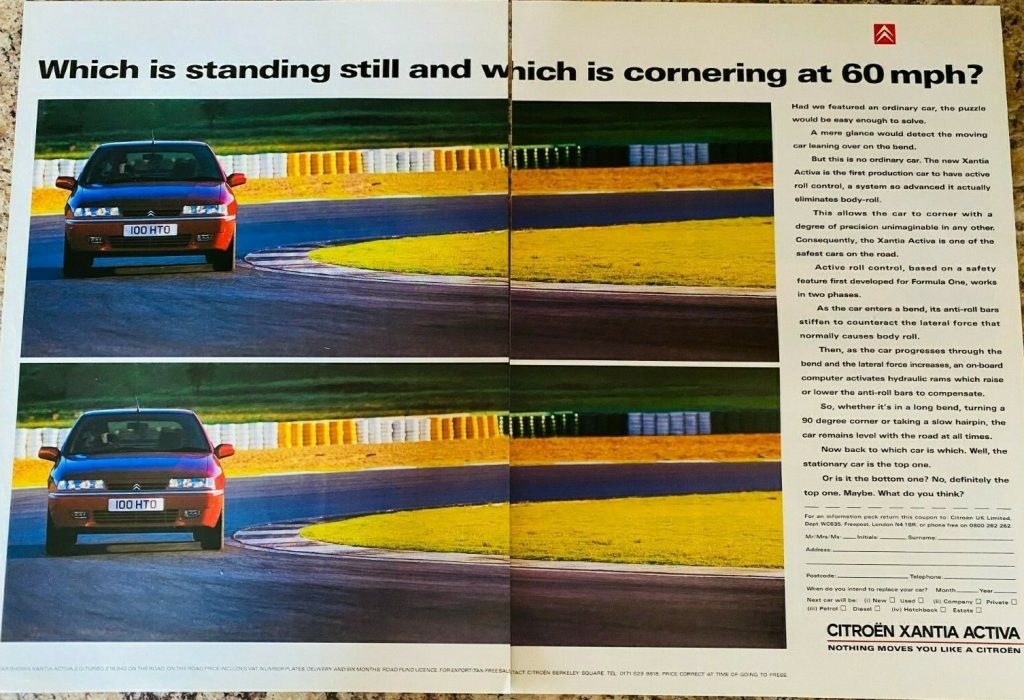

In its print advertising at the time, Citroën showed pictures of two Activas in the middle of a bend and asked which was travelling at 60mph, and which was standing still.

When it went on sale in Britain, in 1996, Autocar devoted six pages to Citroën’s latest – and sadly last – hydropneumatic flirtation with the avant-garde. Journalist David Vivian stuggled to get his head around the Activa. ‘The Activa’s performance is flexible, not fiery. It isn’t very sporty at all. So that makes it a strange animal, indeed: a comfortable family hatch that isn’t quite comfortable enough with a supercar chassis that doesn’t quite work. Perhaps that explains why I like it, but can’t work out why.’

The range-topping Xantia was a car so subtle that even if you saw one, you probably wouldn’t realise. Named after two concept cars, the Activa added a subtle spoiler and wider, five-spoke alloy wheels, and had slightly flared front wings. Early examples only came with two, almost apologetic ‘Activa’ badges on the front doors’ rubbing strips, making it a true Q-car.

The Activa’s appeal lay in its mechanics. Not so much under the bonnet, for the Turbo CT (Constant Torque) was a low-pressure turbocharged 1998cc, 8-valve XM hand-me-down with Peugeot 305 parentage. Toting diesel-like driving characteristics, it realised 173lb ft at 2500rpm and 150bhp at 5300rpm.

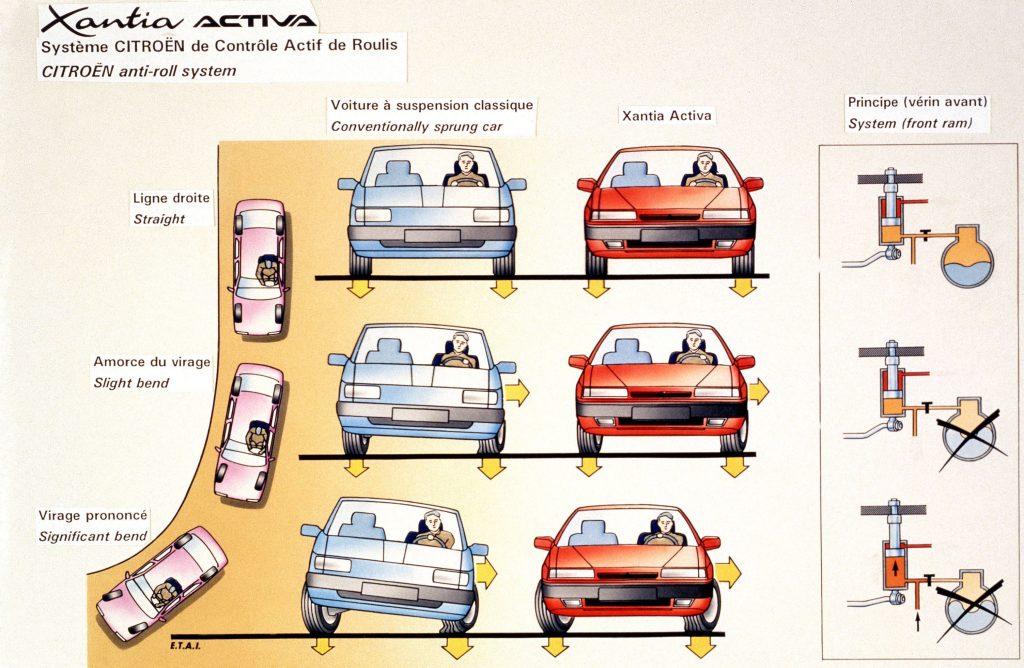

No, the real magic was its suspension, which wasn’t just the ultimate iteration of Hydropneumatique — the Paul Magès designed system that Citroën pioneered — but it featured a world first, too. An evolution of Hydractive II, the Activa featured active anti-roll bars dubbed Systeme Citroën de Contrôle Actif de Roulis (SC.CAR) which limited body roll. (Unlike Hydractive III, Hydractive II retained its fully inter-connected hydraulic system.)

Rather than being truly active, SC.CAR kept body roll to 0.5 degrees. The system featured two suspension settings (Normal and Sport) utilised three ECUs and sensors, and worked in two stages.

First, the active anti-roll bars doubled their stiffness when turning into a bend by cutting off the softening effect of a suspension sphere. Then, if cornering loads continued to build and more than 0.5 degrees roll was detected, LHM (Liquide Hydraulique Minéral) fluid was fed into rams which adjusted the anti-roll bars to keep the car level. By preventing roll and pitch, SC.CAR was claimed to improve grip by 20 per cent, because it helped the tyres maintain their optimal contact patch with the road surface.

Perhaps this indefinable charm explains why I persuaded my father to chop his Rover in for one. The motive was simple: as a master mariner who would often be working away from home, it would fall on me to ‘look after’ the Activa whilst he was at sea. I was a car-mad owner of a despised VW with a driving licence still in nappies, and was willing to concoct any excuse to borrow the Dante Red dart rather than endure the ‘Stodgevagen’.

Driven with fresh-faced exuberance there was turbo lag, but once you were in the torque zone the Activa was wickedly quick. Admittedly I was too inexperienced to meticulously assess it, but it didn’t matter because over A and B roads it was a revelation. Thanks to its cross-country appetite and featherweight controls, journeys were dispatched with a casual shrug. Indeed, if a Gareth Cheeseman salesman type were foolish enough to overtake the Activa, then their bewildered eyes would burn brightly in the rear-view mirror, as if howling, ‘How!?! How is that ruddy French taxi doing that…?’

However, the Activa had its limits. And in my case I tripped over them during a ‘trip to a car show’ which was, in truth, a trackday at Castle Combe race circuit, in Wiltshire.

I knew the circuit and I knew the car. What I didn’t know was how overconfidence can be a very dangerous thing.

Blasting through Quarry and flying along Farm Straight, long before the chicanes were installed, Old Paddock Bend was where the Activa lost interest. The syrupy steering felt as if the wheels had fallen off. That PSA chassis then did what PSA chassis loved to do, and the ensuing 80mph tank-slapper led to a spin à grande Vitesse. I felt as if the Citroën had abandoned me. As we hurtled sideways toward a grass ridge, I waited for the world to flip upside down. Yet by some miracle, we stopped just short. Dad’s car was still intact.

The big downside to Activa ownership, though, was that even then few knew how to look after it and obtaining spare parts was laughably difficult. At just five years old, the Activa needed a refurbished alternator because the dealer couldn’t source a new one. Miles from home, a catastrophic LHM leak kiboshed the brakes, steering and clutch, turning the road green, my face red and my brow sweaty.

Even when spheres and pipework were replaced, the ride felt gristly. Then the ‘Stop’ light started flickering, meaning that the suspension – which featured a Citroën record of 10 spheres – needed attention. The original Michelin tyres became elusive, so other boots were fitted, but their poor grip ruined the Activa’s party-piece.

All too soon, its terrible residual value – to disinterested punters, it was just another old Citroën – ensured it was worth as much as flat Orangina.

The Activa, after a left-hand-drive V6 evolution and a questionable 1998 facelift, ceased production 20 years ago. Although Citroën didn’t replace it, the Activa did leave a legacy as the world’s first production car with active anti-roll suspension – an idea that has since been utilised by numerous luxury saloons and sporty ‘Chelsea tractors’. Yet Hydropneumatique was pensioned off by Citroën five years ago.

After 14 years and 75,000 miles, ‘my’ Activa would die doing something Activas weren’t supposed to do. Like all Xantias the handbrake operated on the front discs, and it wouldn’t hold once the discs had cooled. The Old Man ignored advice to ‘always leave it in gear’ one time too many and so, with some irony, the anti-roll pioneer rolled down a hill with only gravity at the wheel. The poor thing met its end in the surly embrace of a Victorian wall – battered, bruised and many inches shorter.

Today Activas are horribly thin on the ground and rarely come up for sale. Yet, just in case one does, I still have a couple of dusty bottles of Liquide Hydraulique Minéral waiting in the garage…

Read more

French revolution: 5 game-changing Citroëns

£87k Clio V6 tops Renault Collection sale

Your Classics: Mike McDonald and his Citroën Traction Avant once owned by Dave Davies of the Kinks

Not an ‘engineer’ just ‘a humble housewife’ but I am MADLY IN LOVE with Citröen DS and and Xantia.

I was just reading an article about the new Porsche anti-roll suspension system that led me to this article. I had an Activa briefly for around a year curtailed by lack of income as a single householder combined with a lowly mpg of around 25mpg compared with 40 to 45 for the 1.9 turbo diesel. The ride was superb though perhaps the roads weren’t like they are now and having a raz round roundabouts and corners was always great fun.