Author: Bob Merlis

Images: H.B. Halicki Mercantile Company and Joe Wilson

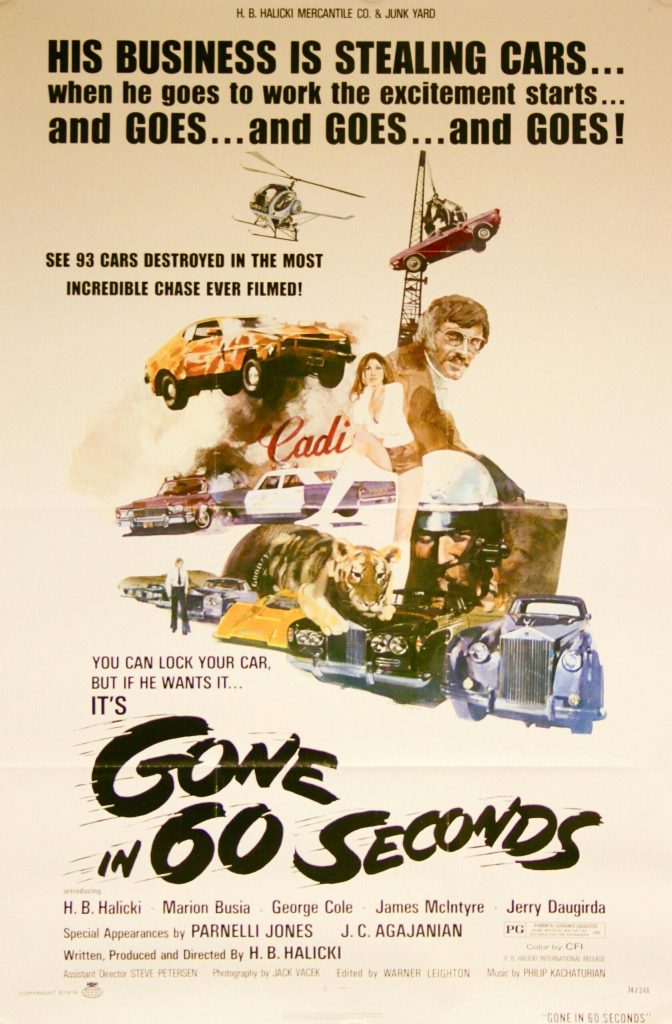

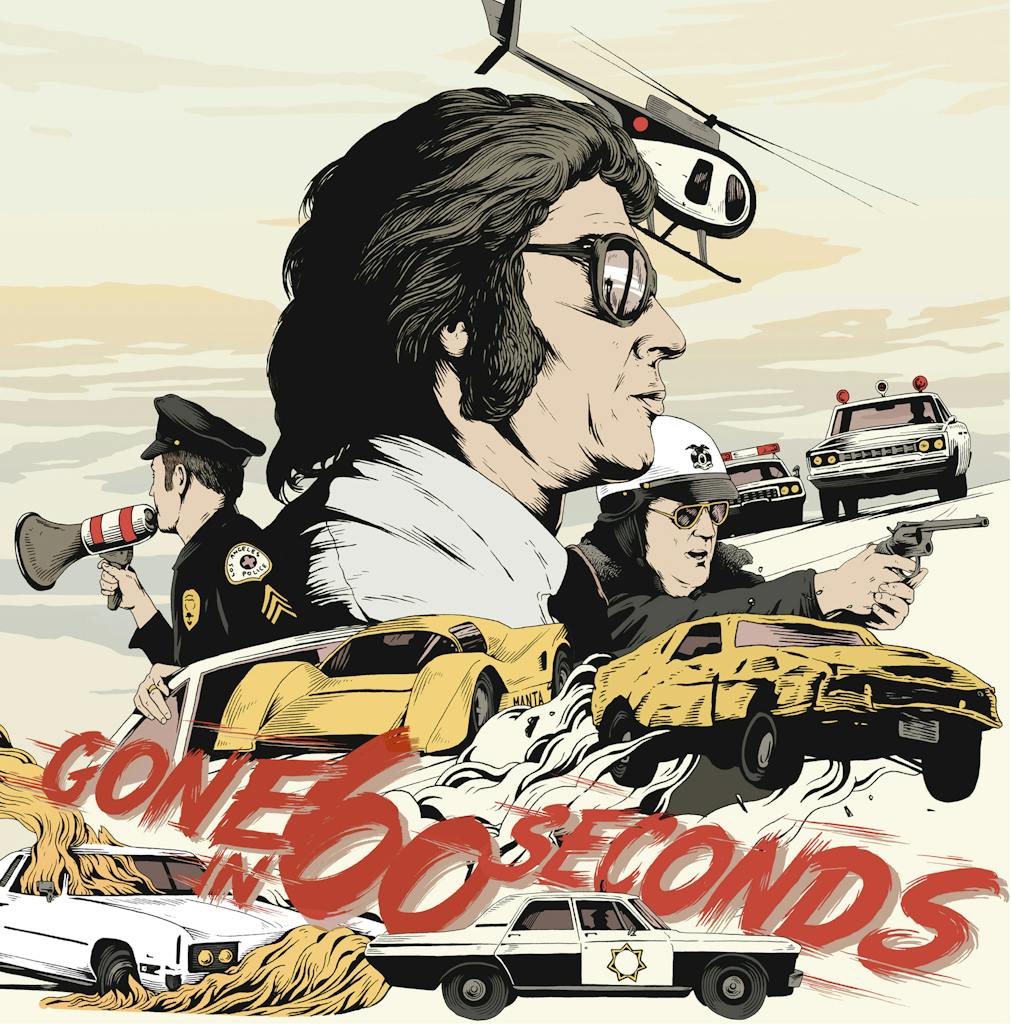

Henry Bernard “Toby” Halicki had a thing about cars. That thing was to destroy them in cinematically compelling ways, not quite inventing, but certainly codifying, a form of popular entertainment. Halicki was not a filmmaker by trade or training, but he took it upon himself to produce, direct, finance, distribute, write (using the term loosely), and star in Gone in 60 Seconds, the car crash epic to end all car crash epics that premiered 50 years ago this past summer. The movie was launched, as were many dozens of on-screen cars seen therein, on 28 July 1974, to be exact.

Crashing cars as entertainment dates to the earlier postwar period. The first instance of car racing as a contact sport might be one staged by Don Basile at Carrell Speedway in Gardena, California, in 1946. Basile went on to become a leading promoter of demolition derbies and even organised an event at the LA Coliseum in early 1973, a year and a half before the release of Gone in 60 Seconds. One of the programme highlights was the destruction of Evel Knievel’s Rolls-Royce. Yes, the early ’70s were a time of ingenuity and innocence, with nary an airbag in sight.

Nowadays, the combination of massive crashes, chases, and pileups on the big screen could be considered earmarks of a film genre unto itself. As cineastes anxiously await the 11th instalment of the Fast & Furious franchise, they may take solace in the fact that this cavalcade of virtually plotless films is a reflection of the vehicular mayhem that was pioneered by Halicki in GI60S. Even films with scripts written by actual screenwriters like Smokey and the Bandit, Mad Max, To Live and Die in L.A., Ronin, and The Blues Brothers owe a huge debt to Halicki, now recognised as a man of vision despite his dispensing with narrative norms.

Most of the modern era’s crashing and smashing is abetted by postproduction digital manipulation that simply didn’t exist a half-century ago when real cars were demolished in real time, and real lives – tragically, including Halicki’s – were at stake. No less a cinematic light than Quentin Tarantino paid overt homage to Halicki when he replicated the GI60S opening scene in his film Kill Bill: Volume 1. Earl McGraw, the Texas Ranger played by Michael Parks, drives a Caprice patrol car, its dashboard festooned with a row of colourful aviator glasses. The opening of GI60S finds Halicki piloting an early ’70s Cadillac Fleetwood Brougham at breakneck speeds to the scene of the derailment. The dashboard is lined with many pairs of his trademark aviator glasses, establishing that he is both idiosyncratic and stylish – and a very fast driver. The man is gone, but his influence abides.

Halicki was born into a 13-sibling family in Dunkirk, New York, where his dad ran a car business (towing, sales, repairs) with young Henry – addressed as Toby by family members for no specific reason – being car obsessed from an early age. Still in his teens, he found his way to Southern California with his Uncle Joe and there he built his own automotive enterprise. It was a towing business and sheriff’s impound lot – known as a wrecking yard in the vernacular – and was located in Gardena, 20 miles and a world away from Hollywood and the same enclave where, coincidentally, Don Basile had made his demo derby bones years before.

The less-than-scenic industrial suburb of Los Angeles might well be sacred ground, as it was also the home of another racetrack, J.C. Agajanian’s Ascot Park. The track was just over the fence from Halicki’s business and was used as a location in the film, as were numerous impromptu settings throughout the greater LA metroplex. He titled the operation “H. B. Halicki Mercantile Co. & Junk Yard” and affected an Old West motif there within. He made his wrecking business a signifier of his innate show-business instincts that fully flowered when he decided he would make a movie. This was, of course, despite the fact that when he started the project, he had no movie-making experience. His actual expertise, along other lines, was useful all the same.

While Halicki’s business prospered and his local real estate holdings grew, he collected cars, toys (100,000 of them at the time of his passing), curios, and, in 1968, an indictment for allegedly being part of a car-theft ring. He was accused of buying cars at salvage yards that would be used to donate VINs and serial-numbered parts to intact cars that had been stolen from LAX and SFO airport parking lots. Although the charges against Halicki were dropped, the same idea – steal cars and switch numbers with wrecked doppelgängers – served as the basic, quasi-autobiographical plotline of Gone in 60 Seconds. The film was reportedly shot for about $150,000 and went on to gross more than $40 million. It spawned the 2000 remake, a Nicolas Cage – ahem – vehicle, but Halicki was long gone by that time. He died in 1989 in a stunt gone awry making his own Gone in 60 Seconds follow-up, appropriately titled Gone in 60 Seconds 2. While on location in Tonawanda, New York, not far from his birthplace in Dunkirk, he was hit squarely by a utility pole brought down by a water tower that had been rigged to collapse after being hit by a truck. Timing was not on his side that day. It’s a cliché to say he died doing what he loved, but it’s true in this case: He loved cars and taking risks and paid the price for his dangerous passion.

“Toby was a real maverick, a guerrilla filmmaker,” his widow, Denice, recalled. “He was a great driver. If he heard a rattle, he’d put someone in the trunk to determine its source.” Seems ironic that the guy who was bothered by an errant rattle had no qualms about wrecking a whole fleet of vehicles. She underscored that whatever you may see in GI60S is what actually happened in that pre-CGI and AI time. “The streets are really the streets, the policemen are really policemen, the firemen are firemen.” She also pointed out the scene in which the mayor of Carson, California, is seen dedicating a sheriff’s substation because, yes, he was dedicating a sheriff’s substation that day, and he really was the mayor. “Toby’s story is the American dream,” Denice told Hagerty. “He wanted to make a movie, and he did just that.” Theirs was a love story, to be sure, and the day they met, Halicki introduced her to Eleanor, the Mustang that had been his GI60S co-star some years earlier.

The “plot” of the original GI60S is clearly an afterthought. Protagonist Maindrian Pace (played by the producer/director) is leading two lives: one as a suave and self-assured insurance adjuster and the other as a savvy chop-shop magnate. For no apparent reason, Argentine gangsters make it worth his while to steal 48 high-end cars over the course of five days. Each of the cars on the shopping list is given a woman’s name as a code, lest the cops listen in and find out what’s going on. One of these cars is, of course, Eleanor, played by a yellow ’71 Mustang SportsRoof visually updated to portray a ’73 Mach 1. There were two Eleanors: the stunt car, which was extensively modified with a full NASCAR roll cage, the transmission welded to the frame, individual rear locking brakes, and a three-inch-thick steel skid plate on the undercarriage to help it survive the film’s climactic 128-foot jump. It was fitted with hood pins to keep the mostly unmodified 351 Cleveland motor from inadvertently stealing any scenes.

The second Eleanor, basically stock, was used for interior shots. The stunt car survives to this day, and let’s recall that 1973 was the last year of the first-generation Mustang before Lee Iacocca introduced the Pinto-based Mustang II to a fuel-starved public. Upon its introduction, Car and Driver posited that it “has about as much technical relationship with its most immediate predecessors as it does with a Sheridan Shillelagh.” The Eleanor-era cars were the biggest “original” Mustangs, more Clydesdale than pony, 800 pounds heavier than the original Falcon-based (1964–69) generation. There was an awareness that a chapter in American muscle car history was about to come to an end. The oil embargo of 1973 was in place when GI60S was filmed, so Eleanor was celebrated as “the last Mustang,” which proved to be temporarily true until the 1979 introduction of the Fox-body torchbearer.

So much for the script, if you choose to call it that; the real raison d’être for the film is to show metal getting bent, twisted, smashed, and pulverised in lots of fascinating ways. Locomotives are made of metal, so early in the film, we’re shown the aftermath of a Santa Fe railroad derailment caused by a collision with a big rig. Halicki merely happened onto the scene and built it into the film. His character is an insurance adjuster, so it seems vaguely logical he’d be investigating the mishap. It would have cost untold thousands to stage a train derailment, and here was Halicki getting it all shot for free, adding that much more reality to the film whose script was not so much written as concocted on the fly, guerrilla-style.

GI60S is a 1970s time capsule: bell bottoms, giant mutton-chop sideburns, bushy moustaches, and pimp-inspired outfits are a visual treat as are the scenes shot at actual automobile dealerships, including the first Mazda store in the United States and Moran Cadillac, both in Torrance, California. The latter was the setting for a scene in which Pace crashes Eleanor into a lineup of new Cadillacs fronting the street. The first few cars were Halicki’s own, but Eleanor hit with such force that some of Moran’s new-car inventory was, shall we say, impacted. It’s not clear if that was disclosed to any of the buyers who drove them off the lot thereafter.

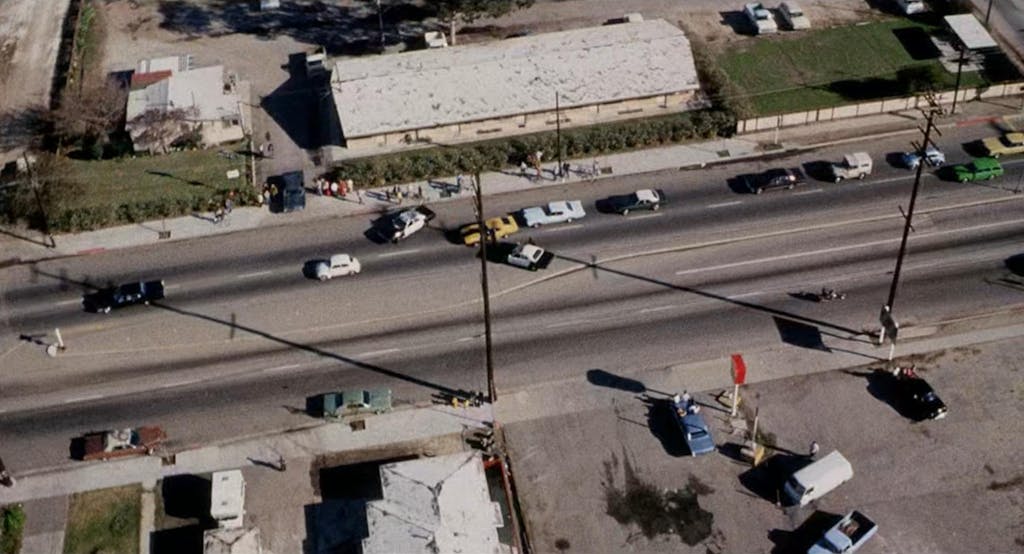

The film was shot, for the most part, without official sanction, often on Sundays when filming permit inspectors were sleeping late and local police enforcement was at a low ebb. Apart from the fact that 93 cars were wrecked or heavily damaged over the course of the filming, it’s worth seeing the film as a real-life period piece. The cars in the film, both in action and parked, are stock (excluding the stunt Eleanor) and offer a picture of Southern California automotive life 50 years ago.

Scenes shot at Ascot Park show the real race fans – not movie extras – who’d come out on a Saturday for a night of midget racing where Pace, cleverly disguised in an Ascot Park windbreaker, steals track owner J.C. Agajanian’s Rolls. We also catch a glimpse of Gary Bettenhausen of Sprint Car, Indy, and NASCAR fame at the track. Another racing notable, the late Parnelli Jones, loses his Big Oly Bronco to Pace’s crew and offers a tour of his facility to Pace, who makes himself right at home in his insurance adjuster guise. Pace was on to something with that acquisition, since the truck, winner of the Baja 1000, Baja 500, and Mint 400, fetched $1.87 million at auction in 2021. Did anybody sign a release? Guessing the answer is somewhere between “Who cares?” and “No.”

One of the film’s highlights, part of the climactic, final 40-minute chase in which whole fleets of squad cars from at least five jurisdictions pursue Eleanor, was unplanned. Pace/Halicki was sideswiped at 100 mph on a freeway ramp by an Eldorado that forced Eleanor into a light pole that toppled aside the ramp. Halicki was initially rendered unconscious and suffered from spinal compression before he came to his “senses.” Eleanor and the fallen pole were carted off by the crew. Friend and neighbour J.C. Agajanian Jr., who is seen in at least two small roles in the film, noted, “He walked different after that.”

Eleanor was made operable a while later and the pole was put back where it fell; the crew feared that Caltrans would replace it while the car was being repaired, which could potentially screw up continuity when filming picked up thereafter. The chase continued with a slow-motion multi-camera shoot climax that included the much-promoted 128-foot jump during which Eleanor came precipitously close to going end over end after soaring 30 feet in the air.

Bearing witness to the automotive carnage are real-life pedestrians seen on city streets and sidewalks that were not cordoned off from the action. Liability issues seem not to have been taken into consideration, with bystanders serving not only as bit players and extras but as unwitting set dressing throughout the film. The same goes for the cars that the cast were charged with stealing, as well as presumably civilian vehicles parked on the street or sharing the freeway with Eleanor.

Car people will take special delight – and maybe horror – in viewing the period cars that populate the film. There’s a terrific Dodge Challenger that gets VIN-swapped after Pace steals it from the lot at Prince Chrysler-Plymouth in Inglewood, dragging it off at the end of a tow hook with a German shepherd and an outraged security guard in hot pursuit. Pace drives the tow truck with the Challenger flopping around on the hook like a huge fish that fights being reeled in. Of course, he succeeds in landing it, and the numbers are deftly switched out by his team of savvy accomplices.

Southern California was a vanguard import car market at that time, and numerous foreign-made oddities populate the film. If you watch carefully, you’ll see a Renault Caravelle, a Volvo PV544, a Mercury Capri, an MG 1100, and a Ford Cortina. During a wild chase through downtown Long Beach on city streets, the sidewalk, and through a park, a Peugeot 404, a Volvo P1800, a BMW 1800, and a Mercedes 230SL “Pagoda” can all be spied. A Ford Fairlane convertible splits in half – Sawzall at play? – after impact on a bridge approach and a Volkswagen Type 3 is flipped onto its fastback roof.

Targets of the car thieves include lots of Cadillacs, among these a ’73 Fleetwood station wagon conversion; at least four Rolls-Royces; several Corvettes; a Mercedes 300SL; a Lamborghini Miura; three or four Ferraris; a Maserati Ghibli coupe; a few Stutz Blackhawks; a De Tomaso Mangusta; a Jensen Interceptor; and a Manta Mirage. A Manta? What’s that? It’s a California-built fibreglass gullwing, V8–powered kit car that could pass for a Porsche 917 in poor lighting. The one in the film is an inconspicuous shade of safety orange with MANTA in big letters on the side. Of course those South American gangsters just had to have one of those. The cars were celebrities in the film, but there were also celebrities’ cars. Apart from the senior Agajanian’s Rolls and Jones’ Bronco, we are treated to NFL Hall of Famer Willie Davis’ Rolls as well as TV star Lyle Waggoner’s Intermeccanica Italia Spyder, swiped from a car wash across the street from CBS Television City. Like Eleanor, the Italo-American exotic was powered by Ford.

Once filming and editing wrapped, Halicki’s wildcat endeavour, created outside the Hollywood system, couldn’t find a traditional distributor, so it had to be “four-walled,” with theatres rented at the expense of the filmmaker. He took to barnstorming from town to town to drum up interest, with the bashed-up Eleanor pulled on a trailer. In the summer of 1974, Halicki and his “bodyguard,” a specialist in collections named Big Tony, stopped at the Floresta Car Wash in San Leandro, California, to spiff up Eleanor before the film premiered at the Palace Theatre that night. An 11-year-old kid named Johnny Martin happened to be hanging out there because he liked cars. Upon encountering Halicki, Eleanor, and Big Tony, Johnny’s life took a fateful turn. Today Martin recalls, “I was blown away to meet him. I admired the car, and he said, ‘This is not a car. Her name’s Eleanor, and she’s my co-star.’” The die was cast; mesmerised by the smashed-up Mustang and the flamboyant Halicki, young Johnny said that he hoped someday to work in films and perform stunts. Halicki told him to look him up when he turned 18 – and that’s just what he did. Martin got to know Halicki and went on to become an award-winning stunt coordinator. Thus, it was cosmically correct that he served as stunt coordinator for the 2000 remake of GI60S, produced by action film mogul Jerry Bruckheimer and starring Nicolas Cage and Angelina Jolie.

Cage grew up in Long Beach, where some of the original was shot when he was nine years old, and was more than passingly familiar with the Eleanor legend, so it seemed a perfect fit for all involved. Martin took stock of his relationship with Halicki. “On the last day of the film’s run in San Leandro, my mom and dad took me to see it,” he recalls. “It just had a recklessness to it, and I started to think about how this guy put it all together.” He muses, “He had a big ego and had this ‘I’m sure I can do that’ attitude. The man could talk anyone into doing anything, and that’s what he did.” Martin continued, “What he pulled off is impossible to accomplish today,” citing the modern-day reality of permits and locations. And scripts. The original GI60S didn’t really have one of those because, as Denice tells it, “He built the film as he went along.” And the truth is that nobody’s ever groused about the dialogue or the acting abilities of the players because, in a very real way, Eleanor was the true star, with the other characters all in support.

What are your thoughts on the analysis above? We would love to hear at hdc@hagerty.co.uk.