Author: Brendan McAleer

Images: Ernie Nagamatsu Collection

On a weekday evening at 4905 Hollywood Boulevard, around eight or nine at night, the light might be on at Hollywood Motors, a trashcan propping the door open. Passing by, Ernie Nagamatsu would recognise the invitation and stop in for coffee. Max Balchowsky started his day around two in the afternoon, often working long into the night; by nine or so, he was ready for a break and a chat.

So there they sat, the freshly graduated student and the wily old hot-rodder. Sharing stories of racing past and present.

“Max really opened this world to me,” Nagamatsu says. “Now it’s about what I call designated responsibility. I want to take care of this car – a custodian carrying on its racing legacy.”

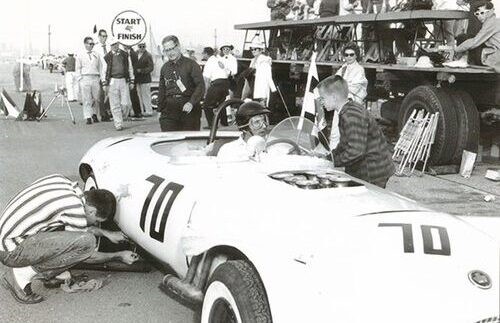

That car is the unlikeliest and most heroic of mutts: Old Yeller II. Ugly, scrappy, brutal, and smarter than you think, this mishmash of fiberglass and Buick V8 has been racing almost continuously since 1959. It still campaigns around the world, Nagamatsu at the wheel, everywhere from Goodwood to Australia.

Nagamatsu says the Aussies cheer for the car just as much as the Brtis and Americans. It’s not hard to see why: In the late 1950s and early 1960s, at a time when pedigreed European marques ruled sports-car racing, a homebuilt special outran the world’s best while wearing whitewall tyres and belching Detroit V8 thunder. The Balchowskys never even owned a trailer, so Old Yeller II would just drive to a track, smoke everybody, then drive home again.

This was the second. There was an Old Yeller I, of course, the first, but also a III, a IV, a V, on up to IX, from 1955 to 1963, each car clearly related to the other, but each also different from the last. For a number of reasons – not least Nagamatsu’s efforts in vintage racing – Yeller II is the one everyone remembers. It is also the one where the world’s best drivers famously begged for a chance behind the wheel. In 1960 alone, its second year of competition, Old Yeller II was piloted by Carroll Shelby, Dan Gurney, Bob Bondurant, and sports-car racing specialist Billy Krause.

If you believe the lore, the way that torque-rich Buick nailhead got up and ran away from the Maseratis and Scarabs at Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, gave Shelby inspiration for what would become the Cobra.

Even as he gained the respect of the giants of the golden age of hot-rodding, Balchowsky kept his cards close to his chest. By the time Yeller II came around, Max and his wife Ina had been swapping engines and tuning racing specials for a decade. Max’s name had never even been on the business. Ina handled invoices but was also a welder and a fabricator. At the races, she was chief mechanic.

They had met in the 1940s, after Max had moved out west to California, following his service in World War Two. Max seems to have been one of those rare natural mechanical intelligences. He had been a belly-gunner on a B-24 Liberator, one of the most dangerous crew positions on that enormous, four-engined bomber. In the war, he had gained a reputation for being able to patch up mechanicals, to keep things going. Ina was a fellow spirit whose father was in the auto-repair business, and the pair began building and servicing cars soon after they met. Racing success came with the couple’s Bu-Ford special, a 1932 Ford Deuce coupe powered by a Buick V8. The recipe would become a Balchowsky trademark.

“In those days, the race courses were on airports,” Nagamatsu says. “So it was basically a drag race between corners. The Buick [engine] had so much torque in any gear.”

Buick V8s had the added advantage of being much cheaper than the more widely loved small-block Chevy – Balchowsky often bragged that he could get a Buick from a junkyard for less than half the cost of a Chevy. Along the same lines, much was made of Old Yeller II’s reputation as a junkyard dog. Balchowsky famously raced on recalled tyres originally meant for a Chevrolet estate, and originally recalled for wearing out too fast. He knew the softer compound meant better grip.

Stories like this gave Old Yeller II a reputation as the ultimate underdog. The plug-ugly aluminium bodywork, the rear panel hammered out of recycled Coke and Pepsi signs, just underlined things. The sum effect was a sort of inverse of Carroll Shelby’s infamous showmanship. Max was more careful than he let on. He stockpiled junkyard parts but used a flow bench to tune and select intake manifolds. He tested tyres with a durometer, and he built in extra cooling for longevity by gifting Yeller II the radiator from of a Studebaker. There was also some extra chassis bracing for driver safety, and even a forward-thinking crumple zone up front. Old Yeller II was a mutt, but a smart one.

The crowds roared their approval. Old Yeller II diced it up with Jaguar D-Types, Ferrari Testarossas, and Maserati Birdcages. Painted with leftover paint in a whitish yellow originally formulated for Ford pickups, it could hang with the world’s best and often beat them. It was a people’s hero.

Yeller II raced into the 1970s, but by that time, the Balchowskys had turned their focus elsewhere. Max was a stunt driver on three Elvis movies, and he kept “Herbie” the Volkswagen Beetle running properly in Disney’s comedy-road-racing hit The Love Bug. Balchowsky also handled the Dodge Challengers in Vanishing Point, and most famously, he set up the Ford Mustang and Challenger for the chase scene in Bullitt.

A friend introduced Nagamatsu to the Balchowskys when Max was in his fifties. At the time, Nagamatsu was living in an apartment just a few blocks from Hollywood Motors. The apartment had almost no furniture because the first thing Nagamatsu did after graduating from dental school was take out a loan on a Mercedes 300SL coupe. To the chagrin of his parents, he owned a Gullwing and one chair. Max and Ernie hit it off.

As the years went by, Balchowsky began to pass on those stories, but also mementos of his racing years. After starting out in Formula Fords, Nagamatsu began vintage-racing a 289 Cobra that Max helped him find and purchase. From time to time, the Nagamatsus would have the Balchowskys over for dinner. After Ina passed away from cancer, Max was often a guest for Thanksgiving.

Max Balchowsky died in 1998, but not before knowing that his most famous creation had gone to the best home possible. Old Yeller II was wrecked in the mid-1970s, then rescued and restored by Dave Gibb of Oklahoma, who took the car vintage racing. Gibb offered it for sale, and was close to making a deal several times; still, he held out for Nagamatsu, for final refusal.

“He knew it was a bit like dog ownership,” Nagamatsu laughs. “He said, ‘Your yard is the best for this dog, instead of an apartment.’”

So, instead of being shut up in a museum, Old Yeller II gets to run. The Nagamatsus have painstakingly brought the car back to its 1959 trim, and they delight in sharing it with crowds. Elaine Nagamatsu knew Max outside of the car world, and she’s the first to suggest heading back to the car, to chat with the fans. Ernie notes that Old Yeller II is a proper people’s car. Folks like to come up and touch it.

The shop at 4905 Hollywood Boulevard is long gone, but Ernie and Elaine have kept the Balchowsky’s legacy alive. Old Yeller II is still out there, still being cheered on, a piece of American racing heritage. Hollywood Motors is a part of the past now, but the light, that invite to stop in, glows on.

What are your thoughts on the above article? We would love to hear from you at hdc@hagerty.co.uk.