Tough?

”You’d better believe it,” says Tom Cox, transmission expert at Pete Cox Sportscars, where he works along with his father.

“We had one customer who lent his racing Triumph TR6 to a friend for a race at Brands Hatch. He didn’t really understand what an overdrive was all about and at maximum revs at the end of the pit straight, he simply clicked it out before Paddock Hill bend. The gearbox instantly saw about 9000 rpm; we did the maths. It completely detonated. There wasn’t anything salvageable, but the overdrive, well, that was fine. We took it apart and put it back together—nothing wrong at all.”

Tough, then, but also ingenious and ubiquitous, the Laycock de Normanville (LdN) overdrive might sound a bit like the transmission equivalent of the Duckworth-Lewis equation, but while it’s not as good at determining the result of a rained-off cricket match, it’s quite brilliant at reducing stress on you and your car when motorway cruising.

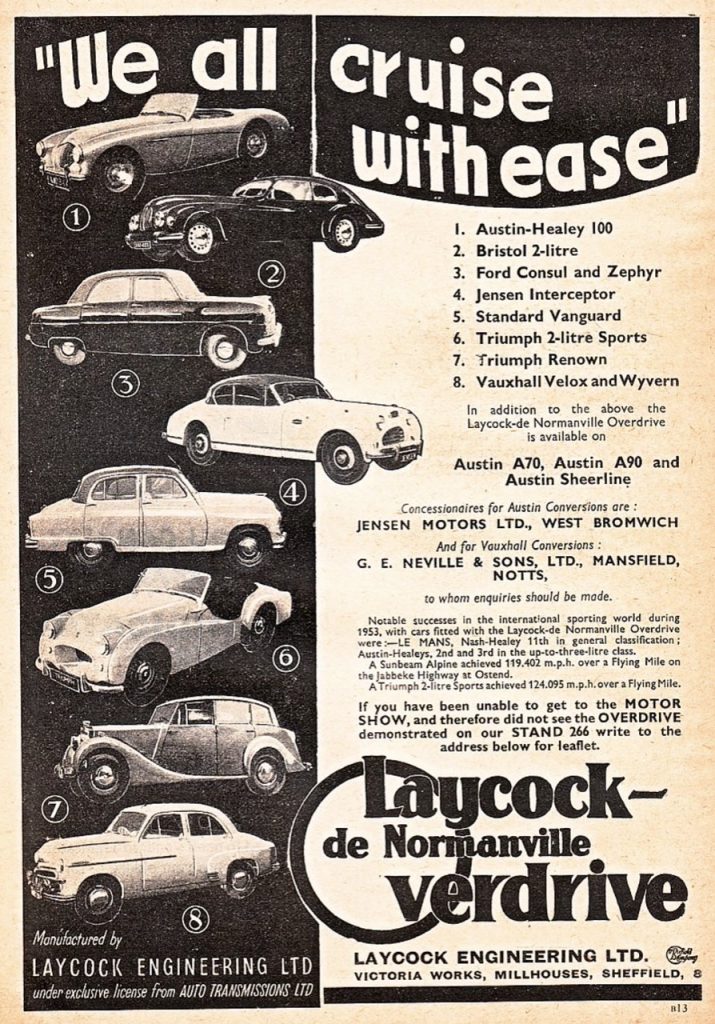

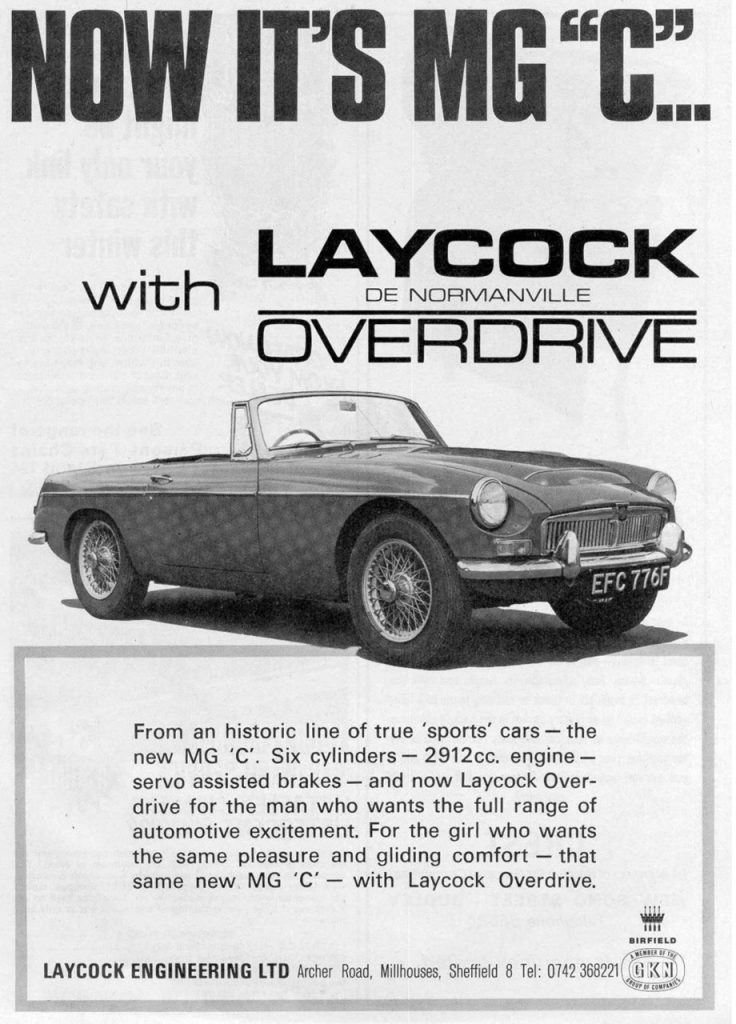

It was invented in 1948 by Edgar de Normanville, an engineer, inventor, and motoring correspondent for The Motor magazine and The Daily Express. He’d already designed a four-speed epicyclic transmission for Humber when he came up with the similarly geared two-speed overdrive unit, which was built by Laycock Engineering in Sheffield. The LdN overdrive was one of a variety of overdrive units, including those from BorgWarner and Fairey, but it was by far the most popular, with an estimated 3.5 million units built over a 40-year period. LdN overdrives saw service on a variety of cars of the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s: Jaguars, Land Rovers, Rovers, Bristols, Austin-Healeys, MGs, Triumphs, Volvos, AMCs, Chevrolets, and even a Ferrari, the 250 GT 2+2.

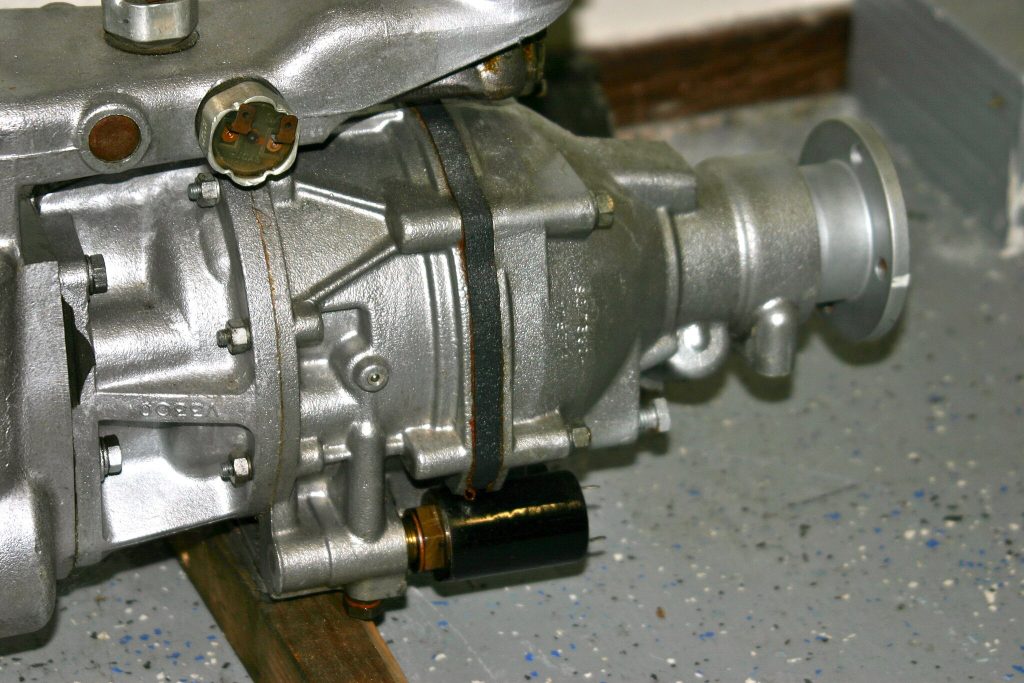

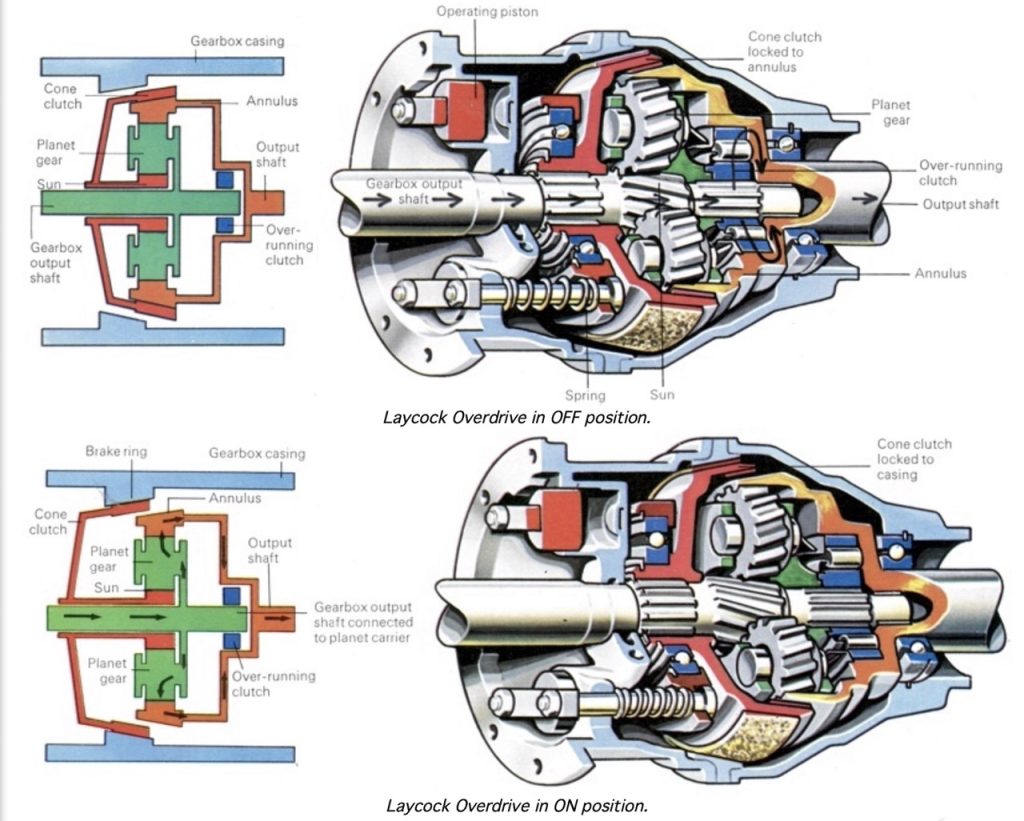

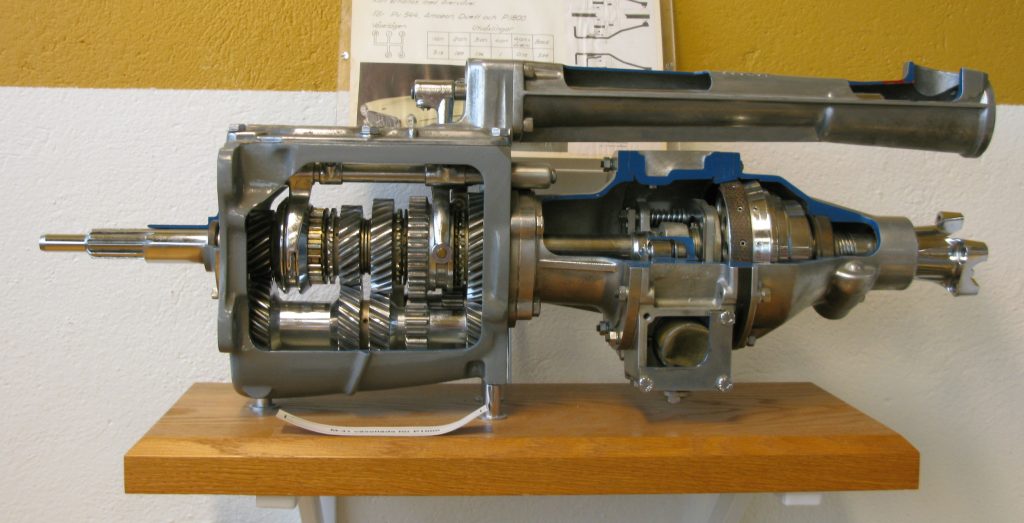

An overdrive unit is essentially a two-speed mechanically/hydraulically activated epicyclic gear system, which is shaped like a misshapen football and bolted to the back of the gearbox driving the propellor shaft. Overdrive simply means gearing that provides a tall enough ratio to enable the output shaft of the gearbox to spin faster than its input. Think of the engine ‘over driving’ the propellor shaft.

So why did cars need overdrives at all? Post-WWII motoring marked a profound change as more middle-class motorists bought cars and travelled farther on very different roads. There were just 383,525 cars on the road in 1923, over a million in 1930, more than 2.5 million by 1950, and just under 5 million in 1960. To enable motorists to travel farther faster, in the 1950s the UK government undertook a program of mass road building to enable a 20th century car-based economy. Britain’s first dual carriageway had opened at the London end of the Great West Road in 1925, but the 1950s and ’60s saw their widespread adoption. In December 1958, the Preston Bypass, Britain’s first-ever motorway, was opened by Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, who quoted Robbie Burns: “I’m now arrived—thanks to the gods! Thro’ pathways rough and muddy. A certain sign that makin’ roads is no this people’s study.”

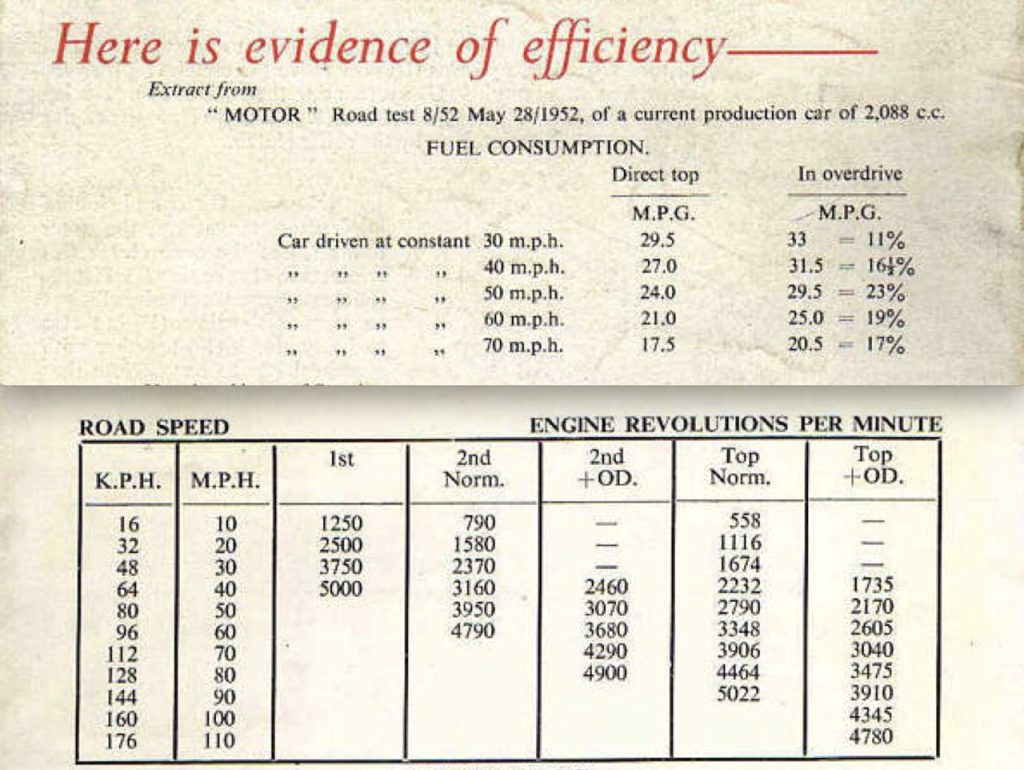

The following year, the first stretch of the M1 opened and cars subjected to the stresses of fast, continuous use on these new roads required a rethink. Better engine bearings, for instance, which could survive that stress, as well as improvements to cooling, better suspension and tyres, and lower cruising revs. With sufficient torque from the engine, fitting an overdrive meant that cars and trucks with longitudinally mounted engines and three- and four-speed gearboxes could drive on these long, straight roads with the engine turning at lower revolutions, which reduced fuel consumption, wear, noise and vibration.

Of course, there was always the option of an over-driven fifth gear, which does much the same thing as an overdrive unit, and that’s exactly where we’ve ended up today with five- and six-speed gearboxes, which reduce the gearing to improve emissions and fuel consumption. In the 1950s and ’60s, however, a five-speed gearbox could be problematic. Designing and manufacturing a five-speed is neither simple nor cheap; witness today where carmakers often hand off their transmission business to firms such as BorgWarner, Dana, Getrag, Voith, Aisin, or ZF and therefore effectively share the cost with other manufacturers.

And, as James Brearley, engineer and director of Overdrive Repair Services in Sheffield says: “That fifth speed would sit at the back of the gearbox, and would need a method to engage it with different shift rods and forks, and there often isn’t the space to accommodate them at the rear of the ‘box.”

So, for the more outward-bound motorist, an overdrive unit it was. And what are those mysterious parts that fill the misshapen football at the back of the gearbox? The basic overdrive parts are the pump, which runs off the gearbox output shaft to build hydraulic pressure, and the solenoid, which opens a valve and allows high-pressure oil to reach the operating pistons, which in turn bear on a cone clutch that locks the epicyclic gearing and engages the taller overdrive ratio.

Although the epicyclic movement of the planets was described in Greek literature and used to illustrate the orbits of those planets, it took the industrial revolution for a generation of engineers to appreciate the benefits of epicyclic gearing: high-speed transmission reduction, with low vibration and relative low cost.

An epicyclic gear system comprises one or more outer planet gears revolving around a central or sun gear, with the planet gears mounted on a carrier, which rotates relative to the sun gear. It’s ingenious and efficient and strong, but complex. I rebuilt the gearbox of my old Triumph, but entrusted the overdrive to a specialist reckoning it was a load of voodoo engineering.

“Yes, there is a certain amount of voodoo in there,” admits Brearley, “though the operating principles are fairly straightforward. They all had their own way of building pressure.”

Initially the LdN overdrive was produced as an A-Type unit. “It has a hydraulic pump unit which built up to 340 to 550psi,” explains Brearley. “That stored pressure, when released, pushed the cone clutch into the brake ring, which stopped the sun gear and sent the drive round the epicyclic gears. In the earliest days the overdrive was controlled by a mechanical lever. The 12-volt solenoid came later.”

Brearley says the A-Type unit had a couple of different ratios, expressed as the percentage reduction in engine revs for a given speed: 22 percent for most Triumphs and 28 percent for Jaguars and Austin-Healeys.

By around 1972, the old A-Types were replaced by the J-Type, which had a slightly different mounting system (more to the rear of the car) and different overall gearing drop. Internet warriors rage about the relative strengths of the A versus J, the latter having smaller gears, fewer moving parts, different hydraulics, which subject the gears to less force, and more accessible hydraulics when mounted in the car.

Different vehicle applications have different adaptor plates and output shafts, and there were also special application overdrives: D-Types for early Triumphs, MGBs, and Hillmans; LH Types for MGBs and Ford-engined vehicles such as the Zephyr and Reliant Scimitar; and the P-Types, which were the last built and fitted to Volvos, keeping the faith in the trusty overdrive by taking over a million units from Laycock.

There were other advantages of the overdrive, too, not least that of providing additional ratios, especially the early A-Type units, which would operate on second, third, and fourth gears. This effectively gave the early TRs seven forward ratios, although third overdrive was so close to fourth as to be practically the same. And some applications, such as the Triumph GT6, gave no advantage in lower engine revs since the £58 special-order overdrive on the 1966 two-seat coupé gave a 0.802 overdriven ratio on third and fourth gears. But it was also accompanied by a final-drive ratio change from 3.27:1 to 3.89:1, which not only required speedo gear change, but also effectively gave the same overall gearing of about 21mph per 1000rpm as the standard four-speed model. So, in this case, the overdrive unit gave substantially better acceleration through the gears over the non-overdrive car.

My own experience is that a LdN overdrive is a reliable if slightly leaky device, and most problems stem from the wiring to the solenoid and neglect of not changing the gearbox oil. Overdrive Repair Services’ Brearley concurs, but says that there are issues with side plates, which come under incredible forces, or the A-Type adaptor plates, which see the same from hydraulic and spring pressure. “It’s unbelievable the pressure those plates have to stand up to, and they bend and crack, so we’ve made up our own stronger items,” he says.

Similarly with linings for the cone clutch, which have had to be remanufactured over the years. Original linings had asbestos content and the new, non-asbestos linings have slightly more grippy characteristics, which means faster and more brutal engagement, which some customers don’t like.

“The clutch has to stop that inertia at quite high engine revs,” says Brearley, “and there’s a slip time which includes the clutch travel and the return rate. If you allow too much slip time, the material can get quite hot quite quickly, so we have to be quite careful. The difference between the clutch thudding in like a ton of bricks and slipping too much can be as little as five-thousands of an inch adjustment.”

There’s also the thorny subject of the right lubrication for the gearbox and overdrive, which share common oil. All are agreed that the most modern GL5 gear oils should be avoided as they can attack some white and yellow metal bearing material. Older GL4 lubricant can be used, but advice from Duckhams, the TR Register, and from Pete Cox is a straight mineral oil SAE 40 change regularly and with cleaned filters at the same time.

Compact five-speed gearboxes and transverse engines put paid to the bulky overdrive, and Laycock closed down in 1970s. “It was a brutal process,” says Brearley. “Specialist machines worth hundreds of thousands and endless overdrive units all went in the skip.” Overdrive Repair Services was born out of that closure and formed by former Laycock engineer Joe Winter in 1986, building on the winding down of Laycock’s repair and spares service. His son Paul joined the company soon after along with Peter Eggington, another former Laycock engineer. “We’re not the only firm looking after Laycock overdrives,” says Brearley, “but we like to think we do a good job.”

It’s easy to see overdrives as heavy and complicated sources of potential breakdown, but however it alters the gearing, in the end, an overdrive is a brilliant driver’s aid in an older car. For overtaking, accelerating and holding a ratio between corners, it has no equal, and that flip of the switch on the steering column (or the gear lever) which engages the voodoo and fires the engine’s revs up or down in the blink of an eye, is one of the great pleasures of an old car.

I spent 13k restoring a Dolomite 1500 and converting it to overdrive was the best thing I did and the greatest change I made.

I fitted a D type to my 1936 2 ltr Triumph Gloria Vitesse Tourer. I removed the freewheel unit from the 4 speed crash gearbox and fitted the O/D using a Spitfire adaptor and a new complete mainshaft supplied by O/D Services.

Made the car more of a pleasure to drive even amongst modern traffic.

Nice simple explanation of the L de N overdrive system. Made sense to the layman. My neighbour has a 1961 Jenson 541s and I wanted to understand how the overdrive worked on his car.

Excellent, glad it worked for you and you learned a few things!